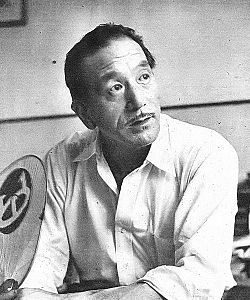

Ophüls was born in Saarbrücken as the son of a Jewish textile manufacturer. He took the pseudonym Ophüls during the early part of his theatrical career so that he wouldn't embarrass his father if he failed. He first worked in the 1920s as actor and then theater director, staging about 200 plays, and made his first film in 1931.

In 1940 he had to flee again, now to the United States, where he experienced the same difficulties as other European directors to fit into the commercialized culture of Hollywood. It would only be in 1947 that he made his first American film (thanks to the help of Preston Sturges), to be followed by three more in the next two years. Two of these films are concise noirs; the best one is based on a story by Stefan Zweig, Letter from an Unknown Woman.

In 1950 Ophüls returned to France where he blossomed again and made his greatest films, four immortal masterworks, until his untimely death from heart disease in 1957: La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952), The Earrings of Madame de... (1953) and Lola Montès (1955), his only film in color. In all, Ophüls made nearly 30 films.

His son, Marcel Ophüls, is a distinguished documentary-film maker.

Characteristic for Ophüls are the following elements:

1. Endlessly mobile camera

All his works feature brilliant long takes, distinctive smooth camera movements, complex crane and dolly sweeps, and tracking shots. In fact, Ophüls' flowing Baroque style of filming is like a Viennese waltz. In his own time, his style was sometimes criticized as "merely decorative," but now we see it has a clear thematic purpose, for example to record the contrast between the protagonists and their emotional problems and the hustle and bustle around them, where life goes on unfeeling. His opulent sets and glittering mirrors in the same way underline the unhappiness of his protagonists. In fact, Ophüls turned his camera into an extension of his characters, visualizing their interiority, adjusting every shot to their minds, desires and lives.

2. Films about women

Besides being the director of romantic regret, of the doomed love story, Ophüls is renowned for his sharply delineated female characters. Many of his films are narrated from the point of view of the female protagonist. In this sense, he made "women's films," but he far exceeded any stereotype of that genre, in fact he is working on the same level as Naruse Mikio and Mizoguchi Kenji.

The best films by Max Ophüls are:

- Liebelei (1933)

The first characteristic film of the great director, based on a play by Arthur Schnitzler. A young lieutenant has an affair with a baroness but falls in love with a violinist's daughter (Magda Schneider, mother of Romy). Although he breaks with the baroness, her husband challenges him to a duel. He is killed and the girl commits suicide. Misplaced male honor leads to tragedy. Tinged with a forlorn mood unique to the director, this film is full of elements that we recognize as truly Ophülsian: settings like the opera house, the army barracks, the bachelor apartment; dances in cafés; a climactic duel, although, as in Madame de... and Letter from an Unknown Woman, we never see the actual killing; the theme of the choice between love and duty. And, at the heart of Liebelei is a woman, who is lured into the trap of fierce passion. This tender story of thwarted love also features several early examples of the director's magically gliding mobile camera. - Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948)

The second film Ophüls made in Hollywood, a bittersweet melodrama. The film already exudes the grace, beauty and sensitivity characteristic of the masterworks he would make in the 1950s in Europe. The story, set in a nostalgic Vienna from around 1900, is loosely based on a story by Stefan Zweig. It is a joke from beyond the grave: a dying woman (Joan Fontaine) sends a long letter to a concert pianist (Louis Jourdan) who is about to flee Vienna to avoid a duel (and as he reads her long letter, he is prevented from leaving...). She has been her whole life in love with him, but was unacknowledged. The pair has crossed paths over many years, although the crossings never lasted more than a few hours. Still the woman, who appears saintly, has born the maestro's illegitimate child. This film has entered the canon and shows that personal expression was possible in Hollywood (though difficult). - Caught (1949)

Caught is one of the two noir films Ophüls made in the U.S., a concise, tense and mean little film, a criticism of capitalism run wild. Leonora (Barbara Bel Geddes), a poor model, dreams of romance, pouring over fashion magazines with mink coats and waiting for her Prince Charming. Then she happens to meet cynical control-freak millionaire Smith Ohlrig (Robert Ryan) - based on Howard Hughes, it is rumored - who marries her as a kind of joke, just to spite his psychoanalyst and to show her he controls her destiny. As a result, Leonora finds herself another piece of opulence stuffed in Ryan's Long Island mansion. On top of that, her husband has a psychotic streak. She tries to run away twice, but each time returns. When she is pregnant, her husband increasingly treats her like one of his many possessions. Struggling slum pediatrician Larry Quinada (James Mason) finally saves her from her Long Island prison, as she has a miscarriage brought on by Ohlig's violence. The film's title "Caught" not only refers to the marriage trap Leonora walked into, but more broadly to the wrong ideas that entrapped her: the materialistic view that money could be the source of all happiness. - La Ronde (1950)

Based on Arthur Schnitzler's notorious play about the vanity and fickleness of love in late 19th c. Vienna. La Ronde presents a series of vignettes between two lovers, with episodes featuring one lover from the previous segment coupled with a new character, a sort of daisy chain structure. Anton Walbrook gives the performance of his life as the master of ceremonies who connects the various episodes. Ophüls shared Schnitzler's vision of the ferociousness of sexual desire, which plays havoc with human beings. But the director shows understanding and forgiveness for the foibles of humankind. We are all weak, so let's smile about life, instead of setting strict rules for others. There is also a bittersweet note, as all romantic illusions of love are shown to be false. At the same time, it is a nostalgic film about European elegance that had been swept away by two terrible wars. The beautiful waltz melody was composed for this film by the last scion of the Strauss family, the at that time 80-year old Oscar Strauss. Ophüls has also assembled a great talented French cast: Simone Signoret, Simone Simon, Gérard Philippe and Danielle Darrieux. - Le Plaisir (1952)

A triptych of stories drawn from the work of Maupassant and demonstrating that "pleasure" is not the same as "happiness." With Jean Gabin, Danielle Darrieux & Simone Simon. The first story ("The Mask") tells of a man who is so addicted to balls and women that he hides his aging face behind a mask - pleasure and youth. The opening sequence is an incredible tour de force of the camera, which follows the swirling beat of a 19th c. ball - typical for Max Ophüls in whose camera movements there is always a visual musicality. But the dancer collapses and is carried home, as the wild dance has become a Dance of Death. The third story ("The Model") is about a painter who falls in love with his model, then dumps her when he grows tired of the affair - the fatality of pleasure when it gives way to boredom. Desperate, she tries to commit suicide by jumping from a window and shatters her legs. But this sacrifice enables her to force the painter into marrying her... The second story, "The Maison Tellier," is the most elaborate, taking up about half of the film. It is about pleasure and purity: how Madame Tellier takes her "girls" (prostitutes) to the country for attending her niece's first communion. It starts with a virtuoso crane shot, inspecting the outside of a bordello and finally gliding into the Maison Tellier. The day trip in the countryside is beautifully filmed (Jean Gabin drives a cartload full of jolly whores, including Danielle Darrieux) and the church scene when all the prostitutes start to cry at the sight of the pure young girls is justly celebrated. We also are present at the ill-fated meeting between one of the prostitutes and the farmer. Ophüls looks with a gentle sense of humor at the proceedings. - The Earrings of Madame de... (1953)

A frivolous woman is transformed by true love. We only get to hear the first name of the heroine of The Earrings of Madame de... - her last name is withheld with a wink. Louise has been indiscreet and as is the case with offenders whose names are withheld in the papers, Ophüls replaces her last name as it were with a few dots or a dash. This films contains some of the best long mobile camera movements Ophüls is famous for: such as the sweeping take when Louise enters the jeweler's shop and ascends via an open staircase to the second floor - not to speak about the incredible dancing scenes with their circling camera. Or, on a different note, the scene where Louise is on a forced trip to the Italian lakes and sits day after day writing letters to her lover, only to confess later to him that she lacked the courage to mail her letters - we see those letters, torn into shreds, dancing in the air, and then turning into the snow falling in the next scene. The story is ingeniously organized around the circulation of a pair of earrings, a present given to Louise by her husband. When she needs money, she sells them back to the jeweler, and then, without knowing this, her lover happens to buy them for her again... The Earrings of Madame De... sets out as a simple comedy of errors but goes on to plumb surprising depths. More than that, like all great directors, in the visual compass of film, Ophüls manages to make life's inexorable flow almost tangible which leaves us as viewers a bit sadder, a bit wiser. - Lola Montès (1955)

Ophüls' only film in color, the tragic story of Lola Montès (Martine Carol), a great adventurer ("the most scandalous woman in the world") who becomes the main attraction of a circus after being the mistress of such famous men as the pianist/composer Franz Liszt and King Ludwig of Bavaria (Anton Walbrook). Taking its cue from La Ronde, we again have a master of ceremonies (Peter Ustinov), who narrates Lola's sensational career as she revolves on a platform in a New Orleans circus. Later the aging courtesan will perform a dangerous trapeze act, and finally the customers will be allowed to kiss her hand after spending a dollar. Ophüls fully employs the devices of circularity and repetition that characterize his late films, as well as the flamboyant cinematic style he had mastered across a lifetime. This is arguably the director's greatest film, a tragic masterpiece that is a summing up of all he stood for. But it failed both critically and at the box-office, which may well have contributed to Ophüls' untimely death in 1957.