Ten Quatrains by Omar Khayyam

tr. Edward Fitzgerald

(1)

I.

WAKE! For the Sun, who scatter'd into flight

The Stars before him from the Field of Night,

Drives Night along with them from Heav'n, and strikes

The Sultan's Turret with a Shaft of Light.

(2)

XXI.

Ah, my Beloved, fill the Cup that clears

TO-DAY of past Regrets and future Fears:

To-morrow—Why, To-morrow I may be

Myself with Yesterday's Sev'n thousand Years.

(3)

XII.

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness—

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

(4)

LXXIV.

YESTERDAY This Day's Madness did prepare;

TO-MORROW's Silence, Triumph, or Despair:

Drink! for you not know whence you came, nor why:

Drink! for you know not why you go, nor where.

(5)

LXXI.

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

(6)

XXXVII.

For I remember stopping by the way

To watch a Potter thumping his wet Clay:

And with its all-obliterated Tongue

It murmur'd—"Gently, Brother, gently, pray!

(7)

LXXII.

And that inverted Bowl they call the Sky,

Whereunder crawling coop'd we live and die,

Lift not your hands to It for help—for It

As impotently moves as you or I.

(8)

VII.

Come, fill the Cup, and in the Fire of Spring

The Winter Garment of Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a little way

To fly—and Lo! the Bird is on the Wing.

(9)

XCVI.

Yet Ah, that Spring should vanish with the Rose!

That Youth's sweet-scented manuscript should close!

The Nightingale that in the branches sang,

Ah whence, and whither flown again, who knows!

(10)

C.

Yon rising Moon that looks for us again—

How oft hereafter will she wax and wane;

How oft hereafter rising look for us

Through this same Garden—and for one in vain!

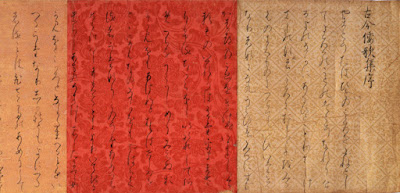

[The Ruba'iyat of Omar Khayyam -

facsimile of the manuscript in the Bodleian Library at Oxford]

Omar (Umar) Khayyam (1048-1131) was a polymath, scientist, philosopher, and poet, born in Nishapur, in northeastern Iran, a leading metropolis in Khorasan during medieval times that reached its zenith of prosperity in the eleventh century under the Seljuq dynasty. His significance in the annals of Islamic intellectual tradition is due to his Rubaiyat (quatrains) and his studies in the field of mathematics. It has often been assumed that his forebears followed the trade of tent-making, since Khayyam means "tent-maker" in Arabic. In his Rubaiyat, Khayyam casts doubt on almost every facet of religious belief, and advocates the drinking of wine.

Scholars have noted that no specific quatrains can confidently be attributed to Omar Khayyam. He certainly may have written quatrains, but then possibly more as an amusement of his leisure hours than as serious poetry. Hundreds of quatrains have been ascribed to him, but it is impossible to disentangle authentic from spurious ones. This is comparable to the Hanshan poems in China, where a corpus sharing similar themes and images also grew exponentially.

Thanks to the popularity of the English translation by Edward Fitzgerald (1859-1889), Omar Khayyam has received popular fame in the modern period. Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat contains loose translations ("renditions") of quatrains from the Bodleian manuscript. It enjoyed great success in the fin de siècle period. I have checked out other translations, old and modern, but Omar Khayyam and Edward Fitzgerald have merged - any other translation sounds wrong and it seems that Fitzgerald has best caught the intentions of the poet.

The Rubaiyat in translation has influenced many other media. I mention here only classical music. The British composer Granville Bantock has produced a choral setting of Fitzgerald's translation (1906-09), a long work for large orchestra, chorus and soloists in a rather heavy, late-Victorian style. It is also quite long as Bantock includes the whole book. I prefer the version by the Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness, who set a dozen of the quatrains to music. This work, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Op. 308 (1975), calls for narrator, orchestra, and solo accordion. The quatrains are narrated, not sung, and the music mostly plays in the intervals between the poems. With an eccentric accordion, and small orchestra, it succeeds very well in invoking Omar Khayyam's world.

[Mausoleum of Omar Khayyam in Nishapur, Iran]

The translations quoted above are by Edward Fitzgerald (the 5th edition of 1889). This translation is in the public domain.

Photos public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

呻

呻