A pleasant surprise: Kazuo Ishiguro, a writer I have been following since his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, in the early 1980s, has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature 2017. I bought his first novel in the Maruzen bookstore in Kyoto when I was living there as a researcher at Kyoto University. Ishiguro has Japanese roots, as his name tells us, but he is not a Japanese author. Born in Nagasaki in 1954, his parents moved to England when he was five because of his father's job. As they expected to return to Japan at some time, in the home they gave their son a Japanese education, while outside the home he learned to be a perfect Englishman (his speech and mannerisms are absolutely English). As it turned out, the return to Japan never came about and Ishiguro obtained English nationality. But like in my own case (having lived for about half my life and almost all of my working life in Japan), his is a hybrid culture, a mix of Japaneseness and Englishness, and that is what makes his novels so interesting. The butler in The Remains of the Day, for example, with his samurai-like loyalty to a worthless master and total neglect of his private feelings, is only conceivable as a fatal combination of English stiff upper-lip and Japanese self-discipline.

Kazuo Ishiguro writes a spare English style, which is both precise and concise. In this respect he can be compared to South-African Nobel Prize winner J.M. Coetzee (another of my favorite writers whom I appreciate for his conciseness). Another connect is that they both have written dystopian novels and fable-like stories. Ishiguro is a great perfectionist in his craft who to date has written only seven novels and one collection of short stories. Despite the austere style, Ishiguro's novels have a great emotional force and, as the Nobel Committee said, "they uncover the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world." His novels often end on a note of melancholic resignation. He engages with memory and forgetting, identity, mortality, and the influence on us of the major 20th/21st c. conflicts - including the comfortable lies people tell themselves to feel like decent persons although they are in fact morally corrupt.

So Kazuo Ishiguro is a major writer with a clear moral stance. His books are serious literature, despite his popularity thanks to the Booker Prize for The Remains of the Day, and the filming of that novel by James Ivory with Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. In fact, his books are not very easy to read. The style is clear enough, but there are always many layers hidden below the narrative which the reader has to uncover in order to be able to appreciate the novel.

The news in Japan was enthusiastic about Kazuo Ishiguro's winning, as he after all was born in Japan and seemed a sort of consolation for the fact that Haruki Murakami again didn't get the prize. The Japanese indeed can celebrate, because Ishiguro is the better writer of the two. This year's Nobel in Literature is an excellent choice (and an intelligent one, as Ishiguro fully deserved it without figuring on any of the outside "bookmaker's" lists) and Kazuo Ishiguro ranks with other recent "deserving" winners as José Saramago, J.M. Coetzee, Orhan Pamuk and Patrick Modiano - to name a few.

October 6, 2017

August 29, 2017

Twentieth Century Opera (6): Oedipus Rex by Igor Stravinsky (1927)

Thanks to Freud's study of the so-called "Oedipus complex," everyone has at least heard the name "Oedipus," a hero from Greek mythology who accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother. The Oedipus story is mentioned in various forms in fragments by Greek poets as Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, Aeschylus and Euripides. The most popular version comes from a set of three "Theban plays" by Sophocles (ca. 496-406 BCE): Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone.

Here is the backstory of Oedipus Rex, which is also used as background in Stravinsky's opera of the same title. Oedipus is the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of the Greek city of Thebes. The famous Oracle of Apollo at Delphi has prophesied that any son born to Laius will kill him. So when Oedipus is born, the royal couple pierces the ankles of the baby so that it cannot crawl (the name Oedipus means "swollen foot") and orders a servant to abandon the child on a nearby mountain. The servant, however, takes pity on the child and gives it to a shepherd from Corinth; finally, via-via, the infant Oedipus ends up being adopted by the childless king and queen of Corinth, Polybus and Merope.

After many years, when he is a grown man, Oedipus accidentally learns that he is not the son of Polybus and Merope and he consults the oracle in Delphi to ask who his true parents are. The oracle only repeats its earlier message to King Laius, "that he is destined to murder his father and marry his mother." In an attempt to avoid such a terrible fate, Oedipus decides not to return to Corinth (believing Polybus and Merope to be his biological parents), but instead to travel to Thebes, a town near Delphi. On the way, at a crossing of three roads, Oedipus encounters a chariot and quarrels with the charioteer over who has the right to go first. When the charioteer tries to run him over, Oedipus kills the man. As we will learn later, this was none other than his father, King Laius. The first part of the prophesy has been fulfilled with ominous speed.

On his way to Thebes, Oedipus encounters a monster called Sphinx, which asks a riddle of all travelers. Only those who can successfully answer, are allowed to pass unharmed, all others are killed. The riddle is: "What walks on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon and three at night?" Oedipus' answer is: "Man: as an infant, he crawls on all fours; as an adult, he walks on two legs; in old age, he uses a walking stick." Oedipus becomes the first traveler ever to answer the riddle correctly.

Now the second part of the prophesy is to be fulfilled. Creon, the brother of Queen Jocasta (and therefore Oedipus' uncle) has announced that the person who manages to vanquish the Spinx will be made King of Thebes, by marrying the recently widowed Queen Jocasta. And so it comes about that Oedipus unwittingly marries the queen, his mother, and has four children by her.

The story told so far is the background to which is constantly referred in both play and opera. Play and opera start from here, again many years later. Thebes has been struck by a plague and its people loudly lament this. Oedipus, king of Thebes and conqueror of the Sphinx, promises to save the city. At his request, Creon seeks the advice of the Oracle of Delphi. The answer is that the murderer of the former King Laius must be brought to justice - he is not just still at large, but even living in the city. It is the murderer who has brought the plague upon the city. Oedipus promises to discover the killer and cast him out. Then the advice of the blind prophet Tiresias is sought. Tiresias at first refuses to speak out and warns King Oedipus not to seek Laius' murderer. Angered, Oedipus accuses him of being the murderer himself. Provoked, Tiresias retorts that "the murderer of the king is a king." Terrified, Oedipus then accuses Tiresias of being in league with Creon, whom he believes is after his throne.

At that moment, Queen Jocasta appears. She calms the quarrel by saying that oracles always lie. After all, wasn't Laius killed at a crossroads by robbers, instead of by the hand of his own son as the oracle had predicted? Filled with foreboding, Oedipus confesses that he, too, has once killed an elderly man at a crossroads. So has he brought about the terrible plague in his own city? A messenger arrives from Corinth to announce the death of King Polybus, whom Oedipus believes to be his father. However, it is now revealed to Oedipus that he is not the biological son of Polybus but a foundling brought up as their own child by the Corinthian royal pair. As proof, the ancient shepherd who took the child to the mountains, is also brought to the palace. Jocasta, finally realizing that Oedipus must be her son, flees. Oedipus misunderstands her motivation, thinking that she feels ashamed of him because he now seems to be of low birth. But at last, the messenger and shepherd state the truth openly: Oedipus is the child of Laius and Jocasta, killer of his father, husband of his mother. He has committed both patricide and incest. Next, the death of Jocasta is reported: she has hanged herself in her chambers. Oedipus breaks into her room and uses the pin from a brooch he takes off her gown to blind himself (he, who was blind to himself, now blinds himself). The Thebans, both sad and angry, ban Oedipus from their city.

[Sophocles - Image Wikipedia]

Here is the backstory of Oedipus Rex, which is also used as background in Stravinsky's opera of the same title. Oedipus is the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of the Greek city of Thebes. The famous Oracle of Apollo at Delphi has prophesied that any son born to Laius will kill him. So when Oedipus is born, the royal couple pierces the ankles of the baby so that it cannot crawl (the name Oedipus means "swollen foot") and orders a servant to abandon the child on a nearby mountain. The servant, however, takes pity on the child and gives it to a shepherd from Corinth; finally, via-via, the infant Oedipus ends up being adopted by the childless king and queen of Corinth, Polybus and Merope.

After many years, when he is a grown man, Oedipus accidentally learns that he is not the son of Polybus and Merope and he consults the oracle in Delphi to ask who his true parents are. The oracle only repeats its earlier message to King Laius, "that he is destined to murder his father and marry his mother." In an attempt to avoid such a terrible fate, Oedipus decides not to return to Corinth (believing Polybus and Merope to be his biological parents), but instead to travel to Thebes, a town near Delphi. On the way, at a crossing of three roads, Oedipus encounters a chariot and quarrels with the charioteer over who has the right to go first. When the charioteer tries to run him over, Oedipus kills the man. As we will learn later, this was none other than his father, King Laius. The first part of the prophesy has been fulfilled with ominous speed.

On his way to Thebes, Oedipus encounters a monster called Sphinx, which asks a riddle of all travelers. Only those who can successfully answer, are allowed to pass unharmed, all others are killed. The riddle is: "What walks on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon and three at night?" Oedipus' answer is: "Man: as an infant, he crawls on all fours; as an adult, he walks on two legs; in old age, he uses a walking stick." Oedipus becomes the first traveler ever to answer the riddle correctly.

[Oedipus and the Sphinx by Ingres - Image Wikipedia]

Now the second part of the prophesy is to be fulfilled. Creon, the brother of Queen Jocasta (and therefore Oedipus' uncle) has announced that the person who manages to vanquish the Spinx will be made King of Thebes, by marrying the recently widowed Queen Jocasta. And so it comes about that Oedipus unwittingly marries the queen, his mother, and has four children by her.

The story told so far is the background to which is constantly referred in both play and opera. Play and opera start from here, again many years later. Thebes has been struck by a plague and its people loudly lament this. Oedipus, king of Thebes and conqueror of the Sphinx, promises to save the city. At his request, Creon seeks the advice of the Oracle of Delphi. The answer is that the murderer of the former King Laius must be brought to justice - he is not just still at large, but even living in the city. It is the murderer who has brought the plague upon the city. Oedipus promises to discover the killer and cast him out. Then the advice of the blind prophet Tiresias is sought. Tiresias at first refuses to speak out and warns King Oedipus not to seek Laius' murderer. Angered, Oedipus accuses him of being the murderer himself. Provoked, Tiresias retorts that "the murderer of the king is a king." Terrified, Oedipus then accuses Tiresias of being in league with Creon, whom he believes is after his throne.

At that moment, Queen Jocasta appears. She calms the quarrel by saying that oracles always lie. After all, wasn't Laius killed at a crossroads by robbers, instead of by the hand of his own son as the oracle had predicted? Filled with foreboding, Oedipus confesses that he, too, has once killed an elderly man at a crossroads. So has he brought about the terrible plague in his own city? A messenger arrives from Corinth to announce the death of King Polybus, whom Oedipus believes to be his father. However, it is now revealed to Oedipus that he is not the biological son of Polybus but a foundling brought up as their own child by the Corinthian royal pair. As proof, the ancient shepherd who took the child to the mountains, is also brought to the palace. Jocasta, finally realizing that Oedipus must be her son, flees. Oedipus misunderstands her motivation, thinking that she feels ashamed of him because he now seems to be of low birth. But at last, the messenger and shepherd state the truth openly: Oedipus is the child of Laius and Jocasta, killer of his father, husband of his mother. He has committed both patricide and incest. Next, the death of Jocasta is reported: she has hanged herself in her chambers. Oedipus breaks into her room and uses the pin from a brooch he takes off her gown to blind himself (he, who was blind to himself, now blinds himself). The Thebans, both sad and angry, ban Oedipus from their city.

[Igor Stravinsky]

The libretto for Stravinsky's opera Oedipus Rex was written by the renowned French poet Jean Cocteau, based on the play by Sophocles. As Stravinsky wanted to create a liturgical "opera-oratorio," he asked for a text in Latin, so Cocteau's French (itself leaning heavily on Sophocles) was translated back into Latin. Stravinsky called Latin not a dead language, but "a language turned to stone." Anyway, to write an opera in Latin could also be seen as irony: how many listeners are really able to understand all those Italian operas? Couldn't they just as well be in Latin? And of course, Latin is also the language in which many Masses, Requiems and other church music have been written in the last few centuries, a language which has an important distancing effect.

The music is in Stravinsky's Neoclassical manner, but with varied fluctuations of mood to fit the dramatic story. The six soloists sing in a somewhat Italianate style and all have their own aria. The opera is however dominated by the male chorus, which comments on events in a heavy declamatory style, giving a decidedly Russian-Orthodox impression. There is also a narrator who is allowed to speak the language of the country where the opera is performed. The narrator introduces the story and returns five or six times to give an update about the action, so that everyone in the public can follow the events on stage. The narration gets gradually more dramatic and is eventually integrated into the musical fabric.

My favorite version of Oedipus Rex is an international Japanese production, which adds elements from Japanese culture to the mix and even features a Butoh dancer (Min Tanaka). This production was directed by Julie Taymor (who also made the film version) and performed at the Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto in Japan in 1992, with Seiji Ozawa as director; soloists are Philip Langridge (Oedipus), Jessye Norman (Jocasta) and Bryn Terfel (Creon); the orchestra and chorus are Japanese. Moreover, the stunning costumes were designed by Emi Wada: the main characters wear a sort of stoneware puppet head on their head (with a primitive face such as have been unearthed by excavations in ancient Greece) and all have huge, hieratic hands of clay; the chorus is clothed in ragged brown sackcloth, which makes them look like resurrected mummies; their make-up is also death-like. Great is also the Japanese narrator, acted by Shiraishi Kayoko, who updates us on the story in what can only be called a super-dramatic style of speaking.

But most interesting is the role played by Tanaka Min. He is a life-size clay puppet wearing a stiff earthen mask, who mimes every gesture of Oedipus with formalized gestures, symbolizing the fact that Oedipus himself is a puppet handled by and at the mercy of the gods. When at the end of the opera the terrible truth about Oedipus becomes known, the clay shell of this puppet breaks and we see a vulnerable, naked man (the only human figure in the whole production). Min Tanaka drives long pins into the eyes of the puppet Oedipus wears on his head and at the same moment strips of red cloth fall like flowing blood from his own blinded eyes. He stumbles down the stage, under which is a pool of dark liquid. Surrounded by ghostly shapes, he walks into the water, the last we see of him. Finally, the sound of dripping water is replaced by that of a cleansing, pouring rain, signaling that the drama is over.

A mix of cultures that works very well, and also a theater adaptation in which always something interesting is happening on stage (if only the mime of Min Tanaka), adding an extra dimension to the original and saving the opera from becoming too static. Musically, it is also an excellent performance.

Twentieth Century Opera Index

August 10, 2017

Modern Japanese Fiction by Year (3): The Years of Aestheticism (1912-1922)

In a literary sense, the Taisho period (1912-1926) is a rich time in which seven of the ten best modern fiction writers from the canon were active (Soseki, Ogai, Kafu, Shiga, Tanizaki, Akutagawa and - just starting at the end of the period - Kawabata). The reign of Emperor Taisho itself was an ambiguous time: some historians talk about "Taisho democracy" and "Taisho chic" and point at political and social trends such as cosmopolitanism that can be linked to the post-1945 democratization of Japan; others, however, see in the Taisho period the roots of radical nationalism, expansionism and anti-liberalism that later marked the 1930s and first half of the 1940s. It is clear that Taisho was a dynamic era.

One function of literature in the preceding Meiji period was the construction and representation of a "modern self," an attempt to situate individual bodies and psyches within rapidly shifting social and cultural fields. Taisho literature is increasingly under the influence of Modernism, in which this process of negotiation breaks down (Seiji M. Lippit, Topographies of Japanese Modernism, p. 7). After all, Modernist writings are characterized by the fragmentation of grammar and narrative and the mixing of multiple genres, as a response to new forms of expression and representation, such as film. Ultimately, this will give rise to a new form of narrative that combines mimesis with ironic self-perception (Tyler in Modanizumu, p. 13).

The Taisho-period novel was dominated by five literary streams, besides that great Meiji authors as Natsume Soseki and Mori Ogai continued writing some of their best works in the first years of the period: 1. The Shishosetsu as an anti-idealistic vehicle, a continuation of Naturalism; 2. The Shishosetsu as practiced by the Shirakaba School, a struggle toward inner peace through emotional crises; note that the discourse on the Shishosetsu was also an attempt to define a "pure literature" (junbungaku) which excluded both political issues and mass culture. Qua style, the Shishosetsu was defined by directness of expression, an unadorned form of Genbun-itchi. 3. The Tanbi-ha or Aesthetic School described below (here we also find Modernist influences), which advocated an adorned literary style and also put emphasis on structure; 4. The Proletarian Literature Movement (described under the year 1923) and the subsequent politicization of literary practice. 5. The development of a mass culture with new forms of entertainment and novels as objects of commerce. From the middle of the 1920s on, popular literature ("Mass Literature," Taishu Bungaku) really took off, for example with the mystery stories of Edogawa Ranpo (see under 1923).

Tanbi-ha or Aesthetic School

Besides the Shishosetsu (both in the Naturalist vein and in the manner of the Shirakaba-ha), the Taisho period is dominated by writers who have been called the Tanbi-ha or Aestheticists. These writers were more concerned with structural form and the beauty of artistic expression than their own way of life, in contrast to the Naturalists (Powell, Writers and Society, p. 85), whom they oppose. The most important writers of this group were Nagai Kafu (who started the trend with his Amerika monogatari and Furansu monogatari), Tanizaki Junichiro, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Sato Haruo, Muro Saisei and Satomi Ton (to be followed in the Showa period by the Shinkankaku-ha of Kawabata Yasunari, Yokomitsu Riichi and others - see under the year 1923). They mainly published in three coterie magazines: Subaru, Mita Bungaku and Shinshicho. They were centered on Keio University in contrast to the Naturalists who were mainly from Waseda University. Western models were Poe and Baudelaire. The literary club in downtown Tokyo where they met was called "Pan no Kai" (Pan Society). Bored with the narrow scope and boring language of the Shishosetsu, they tried to depict the reality of modern Japan in an aesthetically satisfying and logical manner, hoping so to be able to express the consciousness of modern humans.

1912

In July this year, the 45th year of the Meiji period, the Meiji Emperor dies and an epoch comes to an end. 1912 therefore also became known as the first year of the Taisho period - Accession of Emperor Taisho.

"Okitsu Yagoemon no isho" ("The Last Testament of Okitsu Yagoemon") by Mori Ogai. Ogai was deeply moved by the junshi (ritual suicide following his lord into death) of his friend General Nogi on the day of the funeral of the Meiji emperor, 13 September 1912. As a rational, modern man he was shocked by this anachronistic act of self-immolation, by this extreme expression of devotion to "his lord" on the part of someone who was as much part of modern Japan as he was. But Ogai could not simply view this violent act as an aberration, he felt compelled to scrutinize the Japanese past in which such events had happened before. In this story he sympathetically depicts the psychology of a retainer to the Hosokawa house who commits ceremonial suicide following his master's death in 1647. While acting in the course of duty, this retainer finds himself responsible for the unintended death of another retainer. His request to commit seppuku is not granted, and so he waits until he can commit junshi. As a sort of dramatic monologue, Ogai has created a suicide letter in elaborate Tokugawa language. For Ogai, an age had ended and from now on, he would only write historical stories.

[Translated by Richard Bowring in The Incident at Sakai and Other Stories, Hawaii U.P.; Study: Suicidal Honor: General Nogi And the Writings of Mori Ogai And Natsume Soseki, by Doris G. Bargen, Hawaii U.P.]

Natsume Soseki starts serializing Kojin (The Wayfarer). Soseki intensifies his examination of the solitary, intense and even occasionally demented mind. Central to the novel is the marriage of Ichiro and Nao, which is close to collapse. Ichiro and Nao, who married by arrangement, are a classic example of an incompatible couple forced by tradition to live together as husband and wife. Ichiro is on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but the reticent Nao neither argues not complains. Within the bounds of their arranged marriage, both Ichiro and Nao strive to develop their individuality, and so they are stuck between the past with its formalized order and the new individualism of Meiji. Nao is very elusive because she accepts the dictates of tradition, but keeps her heart to herself as a measure of self-protection. Ichiro, from his side, suffers from an excessively cultivated intellect and introspective sensibility. In their type of society, their battle cannot be fought in the open but is a constant silent duel of two minds. The usual love triangle we find in Soseki's novels is made complete by Ichiro's younger brother Jiro (the narrator), who knew Nao before she married his brother and who is the only one in the family who understands and likes her. Nothing happens between them, but several times they come tantalizingly close, especially when a storm forces them to spend the night together in a hotel. Throughout the novel, Jiro also acts as a sort of voyeur, constantly watching Nao and her relation with his brother. But The Wayfarer is more than a novel about a marriage. At the end we get Soseki's philosophy of life, when Ichiro's plight of how to live in the modern world is taken up by a friend who gives him wise advice during a trip together. This advice is "religious" in the general, East-Asian sense: the friend advises Ichiro to surrender rather than assert his ego: through a union with nature, the divine state of individual life, the self can expand and become as large as the universe. This is close to what Soseki later called sokuten kyoshi, "to conform to Heaven and forsake the self." This is the only possibility of salvation for Ichiro, and on a larger scale, modern humans.

[Translated by Beongchon Yu, Tuttle Books; study in Natsume Soseki by Beongchon Yu, Twayne]

Early stories by Tanizaki Junichiro. Tanizaki joined the ranks of first-rate professional writers after publishing only a handful of stories in magazines, on the strength of the critical evaluation of his works by Nagai Kafu. We have already introduced his first story, "Tattoo/The Tattooer" in the previous post.

- "Kirin" (The Kylin, 1910). Confucius visits the State of Wei, where Duke Ling has been enslaved by his beautiful consort Nanzi, a typical Tanizaki-type cruel woman, who even threatens Confucius' state of mind. As the philosopher leaves Wei in defeat, he declares: "I have never yet met a man who loved virtue as much as he loved sex" (an authentic quote from the Master!).

- "Shonen" (The Children, 1911). Three mischievous friends play sadomasochistic games in a mysterious Western-style mansion. Despite its shocking content, this story won Tanizaki critical recognition from Mori Ogai, Ueda Bin and others.

- "Hyofu" (Whirlwind, 1911). A young artist is exhausted after a bout of debauchery with a Yoshiwara oiran and decides to travel to Northern Japan to recuperate. But the call of the blood remains strong... This story was banned and the issue of Mita Bungaku in which it had appeared was taken out of circulation.

"Akuma" (The Devil, 1912). A young man, captivated by a certain lady, steals her handkerchief to savor its odor. She has a bad cold and the handkerchief is dirty, but even so the young man "licks it like a dog." This story earned Tanizaki the sobriquet "Akumashugi," "Diabolist."

- "Himitsu" (The Secret, 1912). A hedonistic narrator experiments with cross-dressing. Guess what happens when in that state he meets the woman who used to be his mistress?

- "Kyofu" (Terror, 1913). The case history of a man with morbidly excitable nerves, who gets attacks of panic when riding streetcars or trains.

[Translations of "The Children" and "The Secret" by Anthony H. Chambers in The Gourmet Club, Kodansha International; "Terror" by Howard Hibbett in Seven Japanese Tales, Vintage]

1913

Mori Ogai writes Abe Ichizoku (The Abe Family), a story in which he renders his views on ritual suicide of retainers more clearly. Using another historical incident in which a number of members of the Abe clan (also retainers to the Hosokawa family) committed suicide in 1641, Ogai creates a grisly account. In comparison to "Okitsu Yagoemon no isho," The Abe Family provides a more ambivalent view of the custom and mentality behind junshi by concentrating on the question of permission for such an act. Ogai remarks aptly that the destruction of the entire Abe family in their mansion resembles "a swarm of bugs in a dish devouring each other." So much for Bushido - the code of behavior is followed, but at the individual's expense. Another "seppuku story" is Sakai Jiken (The Incident at Sakai), based on a historical incident at the beginning of the Meiji period. French soldiers had died in a scuffle with samurai and in answer to the rather exorbitant French demand for reparation, twenty samurai were condemned to ritual suicide. Ogai demonstrates the relentlessness of a system of loyalty and honor that could no longer be sustained. The French Ambassador is forced to watch the suicide, which he does with nausea, as anyone would today. We should note that Ogai does not romanticize the "samurai code" here, there is no infatuation with violent death from his side. He is only trying to understand why men and women of another age could die the way they did, for reasons so alien to the modern rational mind.

[Translated by David Dilworth in The Incident at Sakai and Other Stories, Hawaii U.P.; Study: Suicidal Honor: General Nogi And the Writings of Mori Ogai And Natsume Soseki, by Doris G. Bargen, Hawaii U.P.]

Nakazato Kaizan starts writing his enormous and highly acclaimed novel Daibosatsu Toge (The Great Bodhisattva Pass, 1913-1941). The book won especial fame when Nakazato started writing the second series in 1925. The novel is set against the turbulent political events of the 1850s and 1860s leading up to the Meiji restoration of 1868, which provides historical depth to the story. Its main character is the master swordsman Tsukue Ryunosuke, an amoral, nihilistic antihero who was partly based on Raskolnikov from Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. In a series of loose episodes the author demonstrates man's stubborn blindness to truth. The book was made into a play and - besides influencing the type of nihilistic samurai popular in films in the late 1920s - also many times filmed (by Uchida Tomu in 1957 with Kataoka Chiezo; by Misumi Kenji in 1960 with Ichikawa Raizo; and by Okamoto Kihachi in 1966 with Nakadai Tatsuya).

Nakazato Kaizan (1885-1944) was Japan's first modern popular author ("popular literature" is called Taishu Bungaku, Mass Literature, or Tsuzoku Bungaku, Lowbrow Literature). He was a student of Buddhist philosophy and came to be known as an outspoken pacifist. As a follower of Tolstoy he founded a school based on agrarianist principles.

1914

Japan enters World War I on the side of Great Britain and its allies.

Kokoro by Natsume Soseki. "Kokoro" means "heart," not in the physical sense, but as the "thinking and feeling heart" as opposed to pure intellect. The novel consists of three parts: "Sensei and I," "My Parents and I," and "Sensei's Testament." In Chapter One, the narrator who is a university student in Tokyo close to graduation, befriends a middle-aged intellectual whom he calls "Sensei" - a designation used in Japan for teachers and all kinds of persons with a high status and specialized knowledge, such as doctors and lawyers. Sensei is a married but lonely person who dutifully visits someone’s grave every month alone. In Chapter Two, upon graduation, the narrator returns to his hometown to look after his dying father, who expects him to develop a promising career with the assistance of Sensei. The narrator doesn't feel at home in his parental house anymore, he finds them old-fashioned and narrow-minded. Just when the state of his father becomes critical, the narrator receives a long letter from Sensei. This letter causes the narrator to leave his dying father (thereby creating a situation about which the narrator will feel guilt in the future!) and return to Tokyo hoping he can still see Sensei. In Chapter Three, the letter is given which discloses Sensei's past and expresses his decision to take his own life after the death of Emperor Meiji and the immolation of General Nogi. The story told in the letter is as follows. As a young student, Sensei fell in love with his landlady's daughter, but in his shyness he kept his feelings to himself. Then, at his invitation, his close friend who was in dire straits came to lodge in the same house and, unaware of his feelings, began to love the same girl. Sensei was quick to act when he discovered this. Without saying anything to his friend, he immediately talked to the landlady and obtained her consent for his marriage to her daughter. This is again an example of egoism caused by individualism in Soseki's novels. A few days later, the friend committed suicide. After that, Sensei was never the same - he was never able to free himself from the sense of betrayal and had to live with his heavy guilt for the death of his friend. Sensei, who had lost his faith in humanity after being cheated by his uncle out of his inheritance, was shocked to find the same dark impulses lurking in his own heart. Finally, when he heard the news of General Nogi's suicide to follow the late Emperor Meiji in death at the latter's funeral, he decided to kill himself and thereby end his prolonged agony. In other words, General Nogi's irrational act had opened up a wellspring of emotion in Sensei, that he had assumed to be long since dried up, now enabling him to act on his feelings. As Ueda Makoto says (in Modern Japanese Writers p. 8), "Soseki penetrates deep into the mind of a man faced with a stark human reality: egoism (which led to the betrayal of his friend). The novel is a psychological study of basic human egoism, and a very moving one." Kokoro is generally regarded as Soseki's greatest novel – without exaggeration one can also say, that it is one of the most read novels of the 20th century (more than 705 million copies sold in Japan by 2014, making it the best-selling literary novel of all time). Filmed in 1955 by Ichikawa Kon with Mori Masayuki.

[Translation: Kokoro by Meredith McKinney, Penguin Classics; an older translation is by Edwin McClellan; Study: Suicidal Honor: General Nogi And the Writings of Mori Ogai And Natsume Soseki, by Doris G. Bargen, Hawaii U.P.; Natsume Soseki by Beongchon Yu, Twayne]

1915

Early stories by Akutagawa Ryunosuke.

Here we introduce some famous stories for which Akutagawa sought his material in Japanese history:

- "Rashomon" (1915). Akutagawa's use of the dilapidated Rashomon gate was symbolic, the gate's ruined state representing the moral decay of Japanese civilization in the late Heian period (12th c.). A manservant who has lost his job must choose between honesty and crime. We see how he gradually decides to become a thief, when observing that an old hag in the attic of the Rashomon gate is tearing out the hair of dead bodies dumped there to make wigs. The old woman becomes his first victim, in good Dostoevskian style... Used as the "frame" for Kurosawa's film of the same title.

- "Hana" (The Nose, 1916). Akutagawa's second story, which gained him much fame. A renowned priest with an ugly and hugely long nose after much trouble finally gets rid of his nemesis - but then longs to have it back, as he is nothing special anymore! That the vain and egotistic priest is only obsessed about the state of his nose can be seen as a comment on the relative positions in human society of religion and personal vanity.

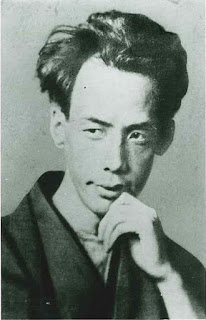

Akutagawa Ryunosuke (1892-1927) was a short story writer, essayist and haiku poet who died young at age 35, but whose about one hundred stories and novellas have become a hard and fast part of the canon of modern Japanese literature, not in the least thanks to his stylistic perfectionism and keen psychological insight. Shortly after Akutagawa was born, his mother went insane, and he therefore was adopted into the family of his maternal uncle, whose surname he assumed. From a young age he was a voracious reader of Western, Japanese and Chinese literature, and at Tokyo University, where he went in 1913, he studied English literature. After graduation, he briefly taught English, before deciding to devote his life to literature. His first published short stories, "Rashomon" (1915) and "Hana" ("The Nose," 1916) drew on both grotesque and comical elements from medieval literature, especially the twelfth century collection of tales, Konjaku Monogatari, and won him encouragement from Natsume Soseki shortly before the latter's death. Over the next five years, Akutagawa maintained his distance from Naturalism, composing short, often fantastic, stories that reworked elements of earlier Japanese, as well as European, literature, which he infused with modern psychology. In the course of the 1920s, as his health declined, Akutagawa turned increasingly to the Shishosetsu mode, writing autobiographical stories, which show his emotional exhaustion. His suicide in 1927 at the age of 35 shocked the literary world and was felt as marking the end of an era, as Akutagawa had been the archetypal Taisho author.

Late stories by Mori Ogai.

- "Sansho Dayu" (Sansho the Bailiff, 1915) is a modern psychological treatment of an old legend found in collections of Buddhist tales. The lyrical story concerns two children, the girl Anju and her younger brother Zushio. While on a journey to search out their banished father, the two children and their mother fall prey to slave traders. Separated from their mother, brother and his sister learn to live in the slave camp, aided by their love for each other. Later on, Anju helps her brother escape, then drowns herself to prevent revealing his whereabouts under torture. Later, Zushio becomes a man of power and is finally reunited with his mother. A classic story, told in simple language, made all the more famous by the great film adaptation by Mizoguchi Kenji, which won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film festival of 1954.

- "Takasebune" (The Boat on the River Takase, 1916) This story gives the exchange between Kisuke, an innocent "criminal" who is mistakenly accused of killing his brother, and the constable Shobe, who has to escort criminals who have been sentenced to banishment out of Kyoto by boat via the River Takase (in fact a canal besides the River Kamo that links up with the River Yodo and so Osaka). Shobe is unable to look beyond his own black-and-white moral values and, although he realizes Kisuke is innocent (the brother has in fact committed suicide), he lacks the courage to act on that.

- "Kanzan Jittoku" (Hanshan and Shide, 1916) is a beautiful laconic retelling of the legend of Hanshan (Kanzan), the legendary author of the famous Zen-inspired "Cold Mountain Poems." According to legend, Hanshan and his sidekick Shide (Jittoku) were recluses who lived deep in the mountains and left their poems on the rocks.

[All 3 stories translated by J. Thomas Rimer in The Incident at Sakai and Other Stories, Hawaii U.P.; "Takasebune" also in The Columbia Anthology I; "Sansho Daiyu" also in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories, ed. Theodore W. Goossen, Oxford U.P.)]

Arakure (The Wild One aka Rough Living) was Tokuda Shusei's most successful Naturalistic novel. It is the story of an exceptionally independent and indomitable woman who refuses to accept the harsh treatment society was accustomed to meet out to such women. When one man after another disappoints her, Oshima casts them aside and moves on. She works hard to move from a life of servitude to one of independence, becoming a seamstress who runs her own business making Western fashion. The sad point is of course that to succeed as an independent subject, in this period a woman has to step outside the bounds of social norms and practices. Tokuda Shusei's Naturalist style was grounded in a populist, lower middle class milieu. Arakure was the most popular novel of the year 1915. In the film Naruse Mikio made in 1957 of this novel, Takamine Hideko gives a wonderful performance of Oshima as a stubborn survivor.

[Translated by Richard Torrance as Rough Living, Hawaii U.P.]

Kanazawa-born Tokuda Shusei (Tokuda Sueo; 1870-1943) is one of the representative writers of the Naturalist movement in Japan. After moving to Tokyo, he started out as a disciple of Ozaki Koyo, before moving on the Naturalism, marked by a realistic style and frank autobiography. Kabi (The Mold, 1911) is his most characteristic Shishosetsu, the story of how he met and married his wife. Shusei is also known for his nuanced treatment of female characters, as in Arakure, an exceptional work written at the time of the decline of the Naturalist school.

1916

Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian to receive the Novel Prize in Literature, makes his first visit to Japan.

Death of Natsume Soseki (1867-1916).

Udekurabe (Rivalry, A Geisha's Tale, 1916-1917) by Nagai Kafu is a magnificent novel about three geishas competing for the same patron, and a vivid picture of how geishas used to live. The three geishas from Tokyo's Shinbashi entertainment district are: the naive and pathetic Komayo; the imperious and spiteful Rikiji; and the crude and gaudy Kikuchiyo. Komayo meets an old patron, Yoshioka, an industrialist, for the first time in a long while. They resume their relationship, but Komayo soon falls in love with Segawa, a Kabuki actor who plays female roles. By way of revenge, Yoshioka shifts his attention to Kikuchiyo, another geisha of the same house as Komayo. Meanwhile, Rikiji, a third geisha who used to be favored by Yoshioka, and was pushed away by Komayo, destroys the relation between Komayo and the Kabuki actor by promoting an affair between him and an ex-geisha who has inherited property. So Komayo looses both her patron and her lover, but luckily the master of the geisha house where she lives takes pity on her and makes her the madam of the house. Komayo and her colleagues are vapid and unscrupulous women, but without idealizing them Kafu manages to make clear why (equally foolish) men are ready to lose their fortunes for such women. Based on Kafu's close observations of the emotions and ways of the world in geisha houses, where he was a habitue himself.

[Translated by Stephen Snyder, Columbia U.P.; this new translation is based on the uncensored Japanese version of the novel and therefore replaces the older translation by Kurt Meisner and Ralph Friedrich (Tuttle); Study in Fictions of Desire, Narrative Form in the Novels of Nagai Kafu, by Stepehn Snyder, Hawaii U.P.]

Last and uncompleted novel Meian (Light and Darkness aka Light and Dark) by Natsume Soseki, who dies this year at the young age of 49 due to an attack of stomach ulcers. Despite its incompleteness, this novel is generally considered as one of the best by Soseki - even in its unfinished state, it is also his longest. The plot evolves around ten days in the life of a young couple, Tsuda and Onobu, who in the short course of their six-month marriage have experienced an increasing tension because of their unyielding egos. Tsuda does not love his new wife but is still in love with a previous flame, Kiyoko, now married to another man. Onobu however does love Tsuda and is determined to make him also love her, challenging the stereotype of the submissive Japanese woman. A dark psychological novel, ending with a mysterious smile.

[Translated by John Nathan as Light and Dark, Chicago U.P.; and by V.H. Viglielmo as Light and Darkness, Tuttle]

Shibue Chusai by Mori Ogai is the first of three long accounts of historical personages from the Tokugawa period, in which Ogai kept as close to the facts as possible. Shibue Chusai is the reconstruction of the life of a doctor in the late Tokugawa period. Chusai (1805-58) was, like Ogai, a doctor in the service of the state and a great lover of the arts. It has been said that in these three biographies Ogai wrote his own spiritual autobiography. However, the accumulation of detail is relentless and only the most determined readers will be willing to follow Ogai here.

[Used by Edwin McClellan as the source for "The Woman in the Crested Kimono," Yale U.P. (McClellan concentrates on the story of the wife of Chusai, Shibue Io, an unusual woman "with an exceptionally keen mind and fearless spirit"]

1917

"Kinosaki nite" (At Kinosaki, 1917), Kozo no kamisama (The Shopboy's God, 1919) and "Takibi" (Bonfire, 1920) by Shiga Naoya. Although Shiga wrote some purely fictional works at the beginning of his career, he is best known for the Shishosetsu-type stories drawn from his life, of which the best ones are perhaps the following three:

- "Kinosaki nite" (At Kinosaki, 1917). The narrator is recuperating at a famous hot spring (Shirosaki in Hyogo prefecture at the Japan Sea) after a near-fatal accident. While there, he witnesses three little deaths - of a wasp, a rat and a lizard - whose ascending scale brings his own brush with death into proper perspective. The rat is stoned by villagers while it tries to swim across a canal with a skewer through its throat; the lizard's death is caused unintentionally by the narrator when he hits it with a stone tossed to make it go into the water. The three encounters also seem to reveal three aspects of death: the repose the narrator imagines will follow death (the dead wasp on the roof of the inn), the instinctual desperation to avoid death (the rat), and the way in which death randomly takes one creature and not another (the lizard). In the narrator's view, humankind is part of a cosmic reality embracing all living things so one should accept one's natural fate with a divine detachment. The inevitable sadness that is part and parcel of being alive suffuses that sense of harmony.

[Translated by Roy Starrs in his study about Shiga Naoya: An Artless Art, The Zen Aesthetic of Shiga Naoya, Japan Library/Curzon Press; also in Lane Dunlop, The Paper Door, Tuttle]

- "Kozo no kamisama" (The Shopboy's God, 1919). A poor shopboy is treated to mouth-watering tuna sushi by a member of the House of Peers who pitied the boy entering the shop without enough money on a previous visit (the aristocrat craves the same sushi, but can't muster the courage to enter a cheap restaurant patronized by commoners). The boy starts thinking of the man as if he were the "Fox God." In a meta-ending, the author briefly intrudes to suggest an alternative plot based on that "Godlike" idea, but then withdraws it and leaves the story as it is, a simple incident.

[Translated by Lane Dunlop in The Paper Door, Tuttle; also in Columbia Anthology I]

- "Takibi" (Bonfire, 1920) In this lyrical (and ultimately plotless) story, set near Mt Akagi in Gunma Prefecture, "nature is not a backdrop for human events, but a vibrant, active force that dwarfs the protagonists, drawing them into its rhythms and mysteries. [...] For Shiga Naoya, the story of the self reaches its ultimate goal when the self disappears within a greater natural reality." (Ted Goossen in his introduction to The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories, p. xxii). The overall mood in the story is one of tranquility and joy, as well as oneness with nature and harmony among humans, such as the four people in the story.

[Translated by Roy Starrs in his study about Shiga Naoya: An Artless Art, The Zen Aesthetic of Shiga Naoya, Japan Library/Curzon Press; also translated as "Night Fires" by Ted Goossen in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories, ed. Theodore W. Goossen, Oxford U.P.)]

Okamoto Kido writes his first Hanshichi stories, about an Edo-period detective, the first Japanese serial investigator – appearing seven years earlier than Edogawa Ranpo's Akechi Kogoro. The Hanshichi stories are intrinsically Japanese. Perhaps Okamoto was indebted to Conan Doyle for the idea of writing detective stories in itself, but the strongest model for Hanshichi are Edo-period crime stories as those about the wise judge Ooka Echizen. Culturally, Japan was not a country of logical reasoning, but rather of intuition, and that difference is clear when you compare Hanshichi to Auguste Dupin or Sherlock Holmes. Hanshichi does not use ratiocination, but rather his intuition plus his detailed knowledge of Edo, the city in which he lived.

[Translation: The Curious Casebook of Inspector Hanshichi: Detective Stories of Old Edo by Ian MacDonald (the first 14 stories). Edgar Seidensticker made adaptations (not translations!) of four stories as The Snake that Bowed.]

Okamoto Kido (1872-1939) was the son of a former senior retainer of the Shogunate. Due to a decline in his family's fortunes, Okamoto could not attend university, but started working as a journalist and reviewer of stage works. The stage was his real love and he also wrote plays himself – his breakthrough came in 1911 with the play Shuzenji Monogatari, which is still occasionally staged. He also wrote modernized Kabuki plays (Shin-Kabuki). Okamoto considered his stage work as his main accomplishment, rather than the detective fiction he wrote. Posterity has judged differently: Okamoto's fame now rests in the first place on his Hanshichi stories, which have never gone out of print and are still available in various editions, from pocketbooks to ebooks.

[Study: Purloined Letters: Cultural Borrowing and Japanese Crime Literature by Mark Silver]

1918

In his middle period, Akutagawa writes several historical stories set in Nagasaki during the period of Christian influence in the late 16th c. He also wrote interesting stories with a contemporary setting.

- "Hokyonin no shi" (The Death of a Disciple, 1918). A young monk, Lorenzo, is accused of being the father of her baby by a girl of the town who is also a believer. He is ordered to leave the Church. When a fire breaks out in the house of the girl, he dashes inside the burning house to save the baby. Severely burned, Lorenzo then dies, and it is revealed when his tattered garment falls apart, that "he" was in fact a "she," and therefore unjustly accused. More stories about Kirishitan by Akutagawa can be found here.

- "Hankechi" ("The Handkerchief, 1916). In a contemporary setting, a woman full of composure relates the death of her son to an aging professor. He notices however that she convulsively clutches her handkerchief and is impressed by this example of "Bushido" by a Japanese woman. But later when he reads Strindberg he finds the statement that an actress who tears her handkerchief while telling about a personal tragedy, is a bad actress... A cynical denial by Akutagawa of the rather superficial belief in (a never-existent) Bushido by Nitobe Inazo.

- "Mikan" (Mandarins, 1919). The narrator, full of ennui, rides a train from Yokohama to Tokyo. In the same compartment is a rather vulgar-looking girl and the narrator is irritated that she obviously sits in the wrong class. At a crossing, she suddenly opens the window and throws some mandarins to her small brothers who are waiting there along the line. The tangerines are spots of color in the dreary landscape. The narrator feels completely revived by this simple scene.

- "Torokko" (The Hand Car, 1922). A boy helps railwaymen push a hand car. At first he is elated by the ride, especially when the car flashes downhill, but after they have traveled a considerable distance the railwaymen tell the boy they are not making a return trip and they leave him beside the tracks. Confused, the boy is overcome by loneliness and fear, as he makes his way home in the gathering darkness. There is a striking semblance between this story and "Manazuru" written two years earlier by Shiga Naoya.

The years between 1914 an 1924 have sometimes been called a "slump" for Tanizaki Junichiro, but nothing could be father from the truth. In these years, Tanizaki experimented with several forms of Modernism, from the detective story to writing film scenarios. In the same years, Tanizaki was active as a playwright, an aspect that is still almost unknown in translation. Some interesting stories from this period are:

- Hakuchu kigo (Devils in Daylight, 1918). A writer is called by his friend, Sonomura, who likes to play the amateur detective but also has a history of mental instability, that he knows exactly when and where a murder will take place that night - if they hurry they can witness it. They stake out the secret location and through peepholes in the knotted wood, become voyeurs at the scene of a shocking crime... But things turn out very different from what they seem to be.

- "Fumiko no Ashi" (Fumiko's Feet, 1919). An old man, infatuated with the beautiful feet of his young mistress, asks a painter to paint her portrait in such a way that her feet are displayed to advantage. When the old man lies dying, he obtains bliss by having Fumiko's foot press against his forehead. Foreshadows Tanizaki's Diary of a Mad Old Man.

- "Tojo" (On the Road, 1920). The story of an almost perfect crime. A man's wife dies of apparently natural causes, but a suspicious detective succeeds in tracing step by step how the man plotted to get rid of his wife so that he could marry a more attractive woman.

- "Aoi hana" (The Blue Flower aka Aguri, 1922). A man is drained of health by a vampirish young mistress (a precursor of Naomi in Chijin no Ai) with whom he is shopping for Western clothes in the foreign quarter of Yokohama. As the male protagonist deteriorates during the shopping expedition, his demanding mistress Aguri flourishes. The story is characterized by motifs all relating to corporality.

- Tomoda to Matsunaga no hanashi (The Strange Case of Tomoda and Matsunaga, 1926). A farcical story in which Tanizaki creates a man who alternates between his thin, quiet and retreating Japanese personality (Matsunaga) and his robust Western and cosmopolitan self (Tomoda), who gregariously travels the world under various aliases. The novella has interesting things to say about how East and West are stereotypically defined and then proceeds to parody these stereotypes. It is also a delightful piece of detective fiction in which Tanizaki's alter ego sleuths on behalf of Matsunaga's wife, who is mystified by her husband's periodic disappearances. As the dual personalities inhabit the same body, there is also an echo of Stevenson here, but without the sinister consequences. As William J. Tyler (in Modanizumu, p. 332) concludes, "Tanizaki's story is a fanciful disquisition on the desire of Japanese to be thoroughly modan, cosmopolitan, and capable of swimming in social circles around the globe."

[Devils in Daylight has been translated by J. Keith Vincent, New Directions; The Strange Case of Tomoda and Matsunaga has been translated by Paul McCarthy in Red Roofs and Other Stories, Michigan U.P.; "Aguri" by Howard Hibbett in Seven Japanese Tales, Vintage and also in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories, ed. Theodore W. Goossen, Oxford U.P.)]

1919

As a victor nation in World War I, Japan is a signatory to the Treaty of Versailles.

Aru onna (A Certain Woman) by Arishima Takeo. The best-known novel by Arishima Takeo, a moral and psychological melodrama about a strong-willed woman struggling against male-dominated society. It is the history of her loves and her battle against the prejudice and hypocrisy of society in order to live a life true to herself; it is also the history of her defeat. According to Kato Shuichi (A History of Japanese Literature 3, Kodansha International, p. 184) this was a theme much treated by Japanese Naturalist novelists (except that the protagonist here is a woman), but the structure is much better than that of Toson, and the heroine's character is delineated with far greater clarity. Satsuki Yoko is strong-willed but capricious - her weak point is her "passion." She marries a journalist (Kibe) in a love match (rare at the time) but soon gets bored with him and decides to divorce him and return to her parents house. After her parent's death, under family pressure, Yoko agrees to marry a friend of a friend (Kimura) who has settled in Seattle. On the boat to the U.S., Yoko has an affair with the purser (Kuraji); when she arrives in Seattle, she decides not to marry Kimura but return to Japan with Kuraji. They start living together, although Kuraji is still married to someone else. Yoko struggles financially, as she has to look after her three sisters. Kuraji proves unreliable and disappears with a police warrant hanging above his head. Yoko is worn out by her constant struggle to escape conventional society; she falls ill and dies. The protagonist was modeled on Sasaki Nobuko, the ex-wife of Kunikida Doppo. Aru Onna is one of the most successful novels modeled on the European realistic tradition (with unmistakable echoes of Anna Karenina).

(Translation: A Certain Woman by Kenneth Strong, University of Tokyo Press)

Arishima Takeo (1878-1923) was born into a wealthy family in Tokyo. He studied at the Gakushuin Peer's school and after that at the Sapporo Agricultural College. In 1901, he became a Christian under the influence of Uchimura Kanzo. Like Kafu, he studied for several years in the U.S. and also traveled in Europe. In 1910, he was one of the founders of the Shirakaba group and started to write. Instead of Christianity, he now became instead loosely attracted to socialist and anarchistic ideas. He wrote his major works at the end of the decade: Umareizuru Nayami (The Agony of Coming into Existence, 1918), Aru Onna (A Certain Woman, 1919) and Oshiminaku Ai wa Ubau (Love Robs without Hesitation, 1920). In 1922, Arishima, troubled by his bourgeois background, offered his farm in Hokkaido free of charge to his tenants. In the next year, he committed suicide with Hatano Akiko, a married magazine writer - in romantic love, he saw death as the highest fulfillment. His two younger brothers, Arishima Ikuma and Satomi Ton, were also authors. His son was the internationally renowned actor Mori Masayuki.

Denen no yuutsu (Rural Melancholy aka Gloom in the Country) by Sato Haruo. We follow an unnamed narrator (a failed author) who moves to a house in the countryside with his wife, an actress, and two Akita dogs. At first pastoral life seems a romantic dream, but rural life soon turns sour: the house falls apart, the garden is consumed by weeds, there are troubles with the neighbors, and on top of that, it keeps raining all the time... Soon boredom, fatigue and insomnia set in to pester the narrator. As Richie has written (in Japanese Literature Reviewed, p. 268): "Sato had read the fin-de-siecle writers and found himself responding. The result is something like Huysmans in Hachioji."

[Translated by Francis B. Tenny with an introduction by J. Thomas Rimer as The Sick Rose, A Pastoral Elegy, Hawaii U.P.]

Sato Haruo (1892-1964) was a Japanese novelist and poet whose works are known for their explorations of melancholy. As a student at Keio University, Sato Haruo was fond of D'Annunzio and Oscar Wilde, as well as Nietzsche, but in his novels we in the first place find the apathy and world-weariness of Baudelaire's Le Spleen de Paris. Sato Haruo was a friend of Tanizaki and later married Tanizaki's first wife. Among his disciples was Ibuse Masuji. Like his fellow decadent writers in Europe, later in life he became as conservative and patriotic as he once had been bohemian.

Kura no naka (In the Storehouse) by Uno Koji. The story of a man with a passion for buying new clothes (like the author). He is desperately poor, but instead of selling old clothes to buy new ones, he pawns them. Whenever he has the chance, he visits his old clothes in the storehouse of the pawnshop. He has also pawned his futon and his greatest pleasure is to sleep in the pawn house, surrounded by the beautiful kimonos he will never be able to redeem... The sentences are long and the narration is full of digressions, as Donald Keene asserts, but this story - a sort of parody of the Shishosetsu - brought Uno Koji instant recognition. It is also his best story.

[Translated by Elaine Tashiro Gerbert (with another story, Love of Mountains, after which the collection is named, Hawaii U.P.]

Uno Koji (Uno Kakujiro; 1891-1961) was born in Fukuoka and attended Waseda University. Although Uno often used parody and satire, he is generally regarded as a Shishosetsu author in the Naturalist vein. His breakthrough came with Kura no naka in 1919, after which he published regularly in major literary magazines. The suicide of his friend Akutagawa Ryunosuke was a major shock and Uno stopped writing due to health problems for several years. His later stories are all semi-autobiographical.

Yujo (Friendship) is Mushanokoji Saneatsu's best known novel, and another example of the author's narcissism. Playwright Nojima is obsessed with a young woman, Sugiko, whom he believes shares his feelings - as in Omedetaki hito, again mistakenly and against all evidence. Nojima is afraid that his friend Omiya could become his rival in love, so he is relieved when Nojima travels to Paris for study. He proposes to Sugiko, but is refused. Some time later Sugiko travels to Paris... Nojima realizes he has both lost a friend and (an imagined) lover. This novel has not been translated. By the way, it is important to note that the major Taisho novelists never visited Europe or the U.S., in contrast to the Meiji writers Soseki, Ogai and Kafu, "the West" was wholly a fantasy for Mushanokoji, Tanizaki and Akutagawa.

1920

League of Nations established with Japan as permanent member - First celebration of May Day in Japan held in Tokyo's Ueno Park.

Okamezasa (Dwarf Bamboo) by Nagai Kafu is a biting satire of the rich and powerful who frequent the demi-monde. Uzaki Kyoseki is an unsuccessful painter, a man of no distinction whatsoever. He has drifted into this profession because in his youth he became the disciple of a famous painter, though he had no talent. He is devoted to the worthless son of the master, Kan, and helps him each time clean up the mess left after his escapades with geisha and other women (Kan is rather loose in his promises of marriage). Everyone in the novel is corrupt. The master is found selling inept paintings by Kyoseki as his own work. When Kan finally marries, his new wife confesses that she is in fact illegitimate. Her pompous father sells fake antiques. Kyoseki prospers as an art consultant, richly rewarded with bribes, and every day visiting a geisha he has set up in business. This novel full of irony is, according to Donald Keene, "a successful Japanese example of Naturalism in the French style" (Dawn to the West, p. 425). A pity it hasn't been translated yet.

[No translation yet. Study in Fictions of Desire, Narrative Form in the Novels of Nagai Kafu, by Stephen Snyder, Hawaii U.P.]

1921

Prime Minister Hara Takashi assassinated - Crown Prince Hirohito becomes regent to the ailing Emperor Taisho.

The founding of the magazine Tane maku hito (The Sowers) marks the beginning of the Proletarian Literature Movement. It was followed in 1924 by the appearance of the proletarian journal Bungei Sensen (Literary Front) and in 1928 by Senki (Battle Flag). As elsewhere in the world, Marxism did not give rise to any great literature in Japan, but it dominated intellectual circles until the early 1930s as part of a larger sociopolitical effort by socialist writers to improve the position of the working class and to stimulate social revolution through literary activity. In Japan, the catalyst was the depression following WWI and the success of the Russian Revolution. The Proletarian Movement introduced to modern Japanese literature the problems of modern capitalistic society and demanded a redefinition of the artist's role in it. The emphasis was put on class society and class politics. The method of realism based on self-confession was attacked, and the belief in the relevance of pure art was shaken, although most authors rejected the didactic and moralistic attitude of an engaged literature. Although a strong critical force, the movement didn't produce much literature of lasting value and in the early 1930s the movement subsided under government repression. As the best proletarian novels are usually mentioned Taiyo no nai machi (Streets without Sun, 1929) by Tokunaga Sunao, about a strike at a printing company, and Kani kosen (The Factory Ship, 1929) by Kobayashi Takiji (see next post).

Anya koro (A Dark Night's Passing, 1921-1937) by Shiga Naoya. Shiga's only novel is one of the great classics of 20th century Japanese literature. The "long night" of the title stands for the protracted passage of the narrator (Kensaku) through a sequence of disturbing experiences into a hard-won truce with destructive forces within himself. The story follows the life of a wealthy, young Japanese writer in the early 1900s, who faces and survives two crises. The first of these is when his attempts to get married are repeatedly thwarted. He discovers from his elder brother that he is unacceptable to potential brides and their families because he was born as the result of an affair between his mother and her father-in-law (his grandfather). Kensaku was in fact raised by the grandfather, who is now deceased, and still lives in the grandfather's house with Oei, a woman who used to be the mistress of the grandfather. Kensaku next proposes marriage to Oei (for whom he harbors secret feelings) but she refuses him as considering the existing relations, marriage between them would be bizarre. Kensaku eventually succeeds in finding a bride (Naoko) only to face his second crisis: her infidelity, when she takes a young man who is a friend of the family as her lover in his absence. Superficially, the narrator shows no dramatic reaction to these events. He draws away from his "father," indulges in a round of dissolution in the Yoshiwara and cafe bars, goes traveling alone to Onomichi and Kyoto, and so on. He does, however, experience great psychological agitation. Finally, during a trip to a temple on Mt Daisen in Tottori, he is able to recapture a sense of harmony with the world trough a strange and wonderful experience of feeling at one with nature, which leads him at last to redemption. Only by seeking unity with the natural world and subjecting oneself to its laws can one achieve a perspective which will enable one to combat the problems of one's life and gain peace of mind. (This ending resembles that of Natsume Soseki's The Wayfarer). But Shiga in the last few pages pulls the rug from under this ending: the narrator suddenly falls seriously ill, he may not survive, even his wife is called from Kyoto to be near him. So the novel ends in irony and ambiguity...

[Translated by Edwin McClellan, Fontana Press / Kodansha International;

Study: An Artless Art, the Zen Aesthetics of Shiga Naoya, by Roy Starrs, Curzon Press]

1922

Japan Communist Party founded - Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, is completed.

Death of Mori Ogai (1862-1922).

Meido (Realm of the Dead) by Uchida Hyakken is a collection of 18 fantastic tales. All stories are nightmares or visionary dreams, suffused with grotesque imagery rooted in the anxieties and uncertainty of human existence, evoking a horror of death as well as awe of the supernatural. The images in the stories fade into one another like images in a dream. Uchida Hyakken was an important innovator of Japanese Modernism.

[Translation by Rachel Denitto, Dalkey Archive]

Uchida Hyakken (Uchida Eizo; 1889–1971) was born in Okayama to a family of sake brewers. He greatly admired Natsume Soseki and in 1911 became his disciple. Later in life, Hyakken would also work as an editor and proofreader for Soseki's complete works. Following graduation from college he taught at various institutions as a German teacher, but abandoned that career after 1934 to become a professional writer. He wrote stories, essays (for which he is best known), diaries and poetry. One of his essays was adapted into the movie Madadayo by Kurosawa Akira (1993) and concentrates on Hyakken's relations with his students. Hyakken also wrote the story on which Suzuki Seijun's Zigeunerweisen (1980) was based.

Chikamatsu Shuko (1876-1944) writes Kurokami (Black Hair), the story of his relations with a Kyoto prostitute called Osono, perhaps Chikamatsu's best work.

One function of literature in the preceding Meiji period was the construction and representation of a "modern self," an attempt to situate individual bodies and psyches within rapidly shifting social and cultural fields. Taisho literature is increasingly under the influence of Modernism, in which this process of negotiation breaks down (Seiji M. Lippit, Topographies of Japanese Modernism, p. 7). After all, Modernist writings are characterized by the fragmentation of grammar and narrative and the mixing of multiple genres, as a response to new forms of expression and representation, such as film. Ultimately, this will give rise to a new form of narrative that combines mimesis with ironic self-perception (Tyler in Modanizumu, p. 13).

The Taisho-period novel was dominated by five literary streams, besides that great Meiji authors as Natsume Soseki and Mori Ogai continued writing some of their best works in the first years of the period: 1. The Shishosetsu as an anti-idealistic vehicle, a continuation of Naturalism; 2. The Shishosetsu as practiced by the Shirakaba School, a struggle toward inner peace through emotional crises; note that the discourse on the Shishosetsu was also an attempt to define a "pure literature" (junbungaku) which excluded both political issues and mass culture. Qua style, the Shishosetsu was defined by directness of expression, an unadorned form of Genbun-itchi. 3. The Tanbi-ha or Aesthetic School described below (here we also find Modernist influences), which advocated an adorned literary style and also put emphasis on structure; 4. The Proletarian Literature Movement (described under the year 1923) and the subsequent politicization of literary practice. 5. The development of a mass culture with new forms of entertainment and novels as objects of commerce. From the middle of the 1920s on, popular literature ("Mass Literature," Taishu Bungaku) really took off, for example with the mystery stories of Edogawa Ranpo (see under 1923).

Tanbi-ha or Aesthetic School

Besides the Shishosetsu (both in the Naturalist vein and in the manner of the Shirakaba-ha), the Taisho period is dominated by writers who have been called the Tanbi-ha or Aestheticists. These writers were more concerned with structural form and the beauty of artistic expression than their own way of life, in contrast to the Naturalists (Powell, Writers and Society, p. 85), whom they oppose. The most important writers of this group were Nagai Kafu (who started the trend with his Amerika monogatari and Furansu monogatari), Tanizaki Junichiro, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Sato Haruo, Muro Saisei and Satomi Ton (to be followed in the Showa period by the Shinkankaku-ha of Kawabata Yasunari, Yokomitsu Riichi and others - see under the year 1923). They mainly published in three coterie magazines: Subaru, Mita Bungaku and Shinshicho. They were centered on Keio University in contrast to the Naturalists who were mainly from Waseda University. Western models were Poe and Baudelaire. The literary club in downtown Tokyo where they met was called "Pan no Kai" (Pan Society). Bored with the narrow scope and boring language of the Shishosetsu, they tried to depict the reality of modern Japan in an aesthetically satisfying and logical manner, hoping so to be able to express the consciousness of modern humans.

1912

In July this year, the 45th year of the Meiji period, the Meiji Emperor dies and an epoch comes to an end. 1912 therefore also became known as the first year of the Taisho period - Accession of Emperor Taisho.

"Okitsu Yagoemon no isho" ("The Last Testament of Okitsu Yagoemon") by Mori Ogai. Ogai was deeply moved by the junshi (ritual suicide following his lord into death) of his friend General Nogi on the day of the funeral of the Meiji emperor, 13 September 1912. As a rational, modern man he was shocked by this anachronistic act of self-immolation, by this extreme expression of devotion to "his lord" on the part of someone who was as much part of modern Japan as he was. But Ogai could not simply view this violent act as an aberration, he felt compelled to scrutinize the Japanese past in which such events had happened before. In this story he sympathetically depicts the psychology of a retainer to the Hosokawa house who commits ceremonial suicide following his master's death in 1647. While acting in the course of duty, this retainer finds himself responsible for the unintended death of another retainer. His request to commit seppuku is not granted, and so he waits until he can commit junshi. As a sort of dramatic monologue, Ogai has created a suicide letter in elaborate Tokugawa language. For Ogai, an age had ended and from now on, he would only write historical stories.

[Translated by Richard Bowring in The Incident at Sakai and Other Stories, Hawaii U.P.; Study: Suicidal Honor: General Nogi And the Writings of Mori Ogai And Natsume Soseki, by Doris G. Bargen, Hawaii U.P.]

Natsume Soseki starts serializing Kojin (The Wayfarer). Soseki intensifies his examination of the solitary, intense and even occasionally demented mind. Central to the novel is the marriage of Ichiro and Nao, which is close to collapse. Ichiro and Nao, who married by arrangement, are a classic example of an incompatible couple forced by tradition to live together as husband and wife. Ichiro is on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but the reticent Nao neither argues not complains. Within the bounds of their arranged marriage, both Ichiro and Nao strive to develop their individuality, and so they are stuck between the past with its formalized order and the new individualism of Meiji. Nao is very elusive because she accepts the dictates of tradition, but keeps her heart to herself as a measure of self-protection. Ichiro, from his side, suffers from an excessively cultivated intellect and introspective sensibility. In their type of society, their battle cannot be fought in the open but is a constant silent duel of two minds. The usual love triangle we find in Soseki's novels is made complete by Ichiro's younger brother Jiro (the narrator), who knew Nao before she married his brother and who is the only one in the family who understands and likes her. Nothing happens between them, but several times they come tantalizingly close, especially when a storm forces them to spend the night together in a hotel. Throughout the novel, Jiro also acts as a sort of voyeur, constantly watching Nao and her relation with his brother. But The Wayfarer is more than a novel about a marriage. At the end we get Soseki's philosophy of life, when Ichiro's plight of how to live in the modern world is taken up by a friend who gives him wise advice during a trip together. This advice is "religious" in the general, East-Asian sense: the friend advises Ichiro to surrender rather than assert his ego: through a union with nature, the divine state of individual life, the self can expand and become as large as the universe. This is close to what Soseki later called sokuten kyoshi, "to conform to Heaven and forsake the self." This is the only possibility of salvation for Ichiro, and on a larger scale, modern humans.

[Translated by Beongchon Yu, Tuttle Books; study in Natsume Soseki by Beongchon Yu, Twayne]

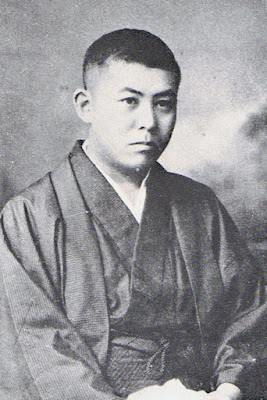

[Tanizaki in 1913]

Early stories by Tanizaki Junichiro. Tanizaki joined the ranks of first-rate professional writers after publishing only a handful of stories in magazines, on the strength of the critical evaluation of his works by Nagai Kafu. We have already introduced his first story, "Tattoo/The Tattooer" in the previous post.

- "Kirin" (The Kylin, 1910). Confucius visits the State of Wei, where Duke Ling has been enslaved by his beautiful consort Nanzi, a typical Tanizaki-type cruel woman, who even threatens Confucius' state of mind. As the philosopher leaves Wei in defeat, he declares: "I have never yet met a man who loved virtue as much as he loved sex" (an authentic quote from the Master!).

- "Shonen" (The Children, 1911). Three mischievous friends play sadomasochistic games in a mysterious Western-style mansion. Despite its shocking content, this story won Tanizaki critical recognition from Mori Ogai, Ueda Bin and others.

- "Hyofu" (Whirlwind, 1911). A young artist is exhausted after a bout of debauchery with a Yoshiwara oiran and decides to travel to Northern Japan to recuperate. But the call of the blood remains strong... This story was banned and the issue of Mita Bungaku in which it had appeared was taken out of circulation.

"Akuma" (The Devil, 1912). A young man, captivated by a certain lady, steals her handkerchief to savor its odor. She has a bad cold and the handkerchief is dirty, but even so the young man "licks it like a dog." This story earned Tanizaki the sobriquet "Akumashugi," "Diabolist."

- "Himitsu" (The Secret, 1912). A hedonistic narrator experiments with cross-dressing. Guess what happens when in that state he meets the woman who used to be his mistress?

- "Kyofu" (Terror, 1913). The case history of a man with morbidly excitable nerves, who gets attacks of panic when riding streetcars or trains.

[Translations of "The Children" and "The Secret" by Anthony H. Chambers in The Gourmet Club, Kodansha International; "Terror" by Howard Hibbett in Seven Japanese Tales, Vintage]

1913

Mori Ogai writes Abe Ichizoku (The Abe Family), a story in which he renders his views on ritual suicide of retainers more clearly. Using another historical incident in which a number of members of the Abe clan (also retainers to the Hosokawa family) committed suicide in 1641, Ogai creates a grisly account. In comparison to "Okitsu Yagoemon no isho," The Abe Family provides a more ambivalent view of the custom and mentality behind junshi by concentrating on the question of permission for such an act. Ogai remarks aptly that the destruction of the entire Abe family in their mansion resembles "a swarm of bugs in a dish devouring each other." So much for Bushido - the code of behavior is followed, but at the individual's expense. Another "seppuku story" is Sakai Jiken (The Incident at Sakai), based on a historical incident at the beginning of the Meiji period. French soldiers had died in a scuffle with samurai and in answer to the rather exorbitant French demand for reparation, twenty samurai were condemned to ritual suicide. Ogai demonstrates the relentlessness of a system of loyalty and honor that could no longer be sustained. The French Ambassador is forced to watch the suicide, which he does with nausea, as anyone would today. We should note that Ogai does not romanticize the "samurai code" here, there is no infatuation with violent death from his side. He is only trying to understand why men and women of another age could die the way they did, for reasons so alien to the modern rational mind.

[Translated by David Dilworth in The Incident at Sakai and Other Stories, Hawaii U.P.; Study: Suicidal Honor: General Nogi And the Writings of Mori Ogai And Natsume Soseki, by Doris G. Bargen, Hawaii U.P.]