Kiritsubo

The title

"Kiri" means "paulownia tree" and "tsubo" is a small garden between the buildings of a palace or temple. So "Kiritsubo" is the name for the Heian Palace pavilion that has a paulownia tree in its garden. It is located in the northeast corner, among all pavilions of the Emperor's women the farthest from the living quarters of the Emperor himself. The Emperor installs Genji's mother here. In later times, Genji's mother was therefore called "Kiritsubo no Koi," the "Intimate of the Kiritsubo," but Murasaki Shikibu doesn't use this designation for her.

"The Paulownia Pavilion" is the translation used by Tyler; Seidensticker has "Paulownia Court," which is just as fitting; Waley leaves the title in Japanese. Only Washburn is a bit cumbersome with his "The Lady of the Paulownia-Courtyard Chambers", although he does bring out the full meaning.

Chronology

Position in the Genji

The Heian Palace not only contained the living quarters for the imperial family (in the northern part, called dairi), but also all government ministries (in the southern part, called daidairi). A combination of the present Prime Ministers Residence with Kasumigaseki, so to speak. Like Gosho, the still existing old palace in Kyoto, it was secured by a mud-wall, and also by a moat. The central southern gate was called Suzaku Gate after the avenue onto which it opened. Close to this gate stood the Daigokuden or Great Hall of State, where all sorts of official ceremonies were held - the heart of governmental Japan in the Heian-period.

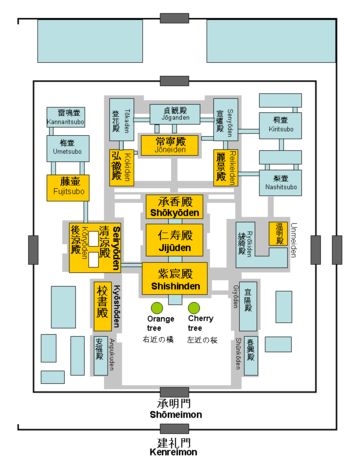

But the Genji of course is set in the Emperor's living quarters. These were in the Jijuden (above the Shishinden) or in the Shokyoden; in later times also in the Seiryoden, to the west of these buildings. Behind them in the most northern part of the palace grounds were the pavilions of the imperial consort and concubines. The principal consort lived in the Kokiden (after which she is named in the Genji), close to the Emperor's quarters. The Kiritsubo Pavilion where the low-ranked mother of Genji lived, was in the far upper right corner. The second favorite of the Emperor, Fujitsubo, managed to get a pavilion closer to him, in fact on the west side immediately above the Seiryoden, so even closer by than the Kokiden.

The palace compound fell victim to repeated fires. After a big conflagration in 1177, the Daigokuden was not rebuilt. The compound itself was definitively abandoned in the mid-fourteenth century, when a location further east was found – the present Kyoto Gosho. The palace in fact followed the city, of which the center had also moved east.

The second point is that these imperial women were not equal, but like everyone in Heian society had to obey a strict hierarchy. (In fact, your birth decided your life in Heian times.) So below the single Empress (called Chugu) the Emperor would have several Consorts (Nyogo) and, lower still, a certain number of Intimates (Koi). An Empress was usually appointed from among the Consorts, but not all Consorts had a realistic hope of such a success, as it depended on family relations (i.e. a male family member with a powerful position at court). The Intimates could never become Empress, their birth rank was too low and they lacked sufficient political support. That is not to say that these ladies were really very low in status - while the Nyogo had fathers who were of ministerial rank, the fathers of the Koi were only just below that, as counselors or chunagon. But they obviously had much less power at court.

Talking about the power of the families of the imperial women, we also have to mention the fact that during much of the Heian period, the Fujiwara family managed to dominate Japanese politics through the strategy of marrying Fujiwara daughters to emperors. In that way the Fujiwara would gain influence over the next emperor who would, according to the family tradition of that time, be raised in the household of his mother's side and owe loyalty to his maternal family. Moreover, the father of the daughter who became empress, would monopolize the position of regent (sessho or kampaku). He would rule on behalf of the new emperor as long as that person was still a child or very young man – and when the emperor who never had any power himself, became an adult, he would be forced to abdicate and the next child-emperor would be installed under the tutelage of the same or another Fujiwara regent.

Now the Genji starts with the situation that the Emperor can not control his amorous feelings for one of his concubines, the low-ranking Intimate (koi) Lady Kiritsubo, named after the pavilion where she lives, with a paulownia tree (kiri) in the small courtyard garden (tsubo). The fact that her rooms are farthest from the imperial chambers also indicates her low status. But that does not hold the Emperor back, on the contrary: deeply in love, he favors her above all his other wives, including his primary consort, Lady Kokiden, the daughter of the powerful Minister of the Right (she is the main Consort, but there is no official Empress at this time). This provokes the fierce jealousy of the other imperial concubines. Lady Kiritsubo is disadvantaged because of her low rank and lack of parental support (her father is already deceased), so she is constantly harassed by the other women. Her only support is the Emperor's personal devotion, but that is not enough. The humiliations she has to suffer make her waste away and finally trigger her premature death.

But the union between the Emperor and Lady Kiritsubo has by then already born fruit: three years before her death, a son has been born, a most handsome boy: our Genji. After the death of his wife, the Emperor dotes on the boy, who is nicknamed "Hikari," "the Shining." He is so handsome that he hardly seems of this world.

By the way, both such a birth and illness could not take place in the palace. Both birth and illness (or death) were considered as polluting and therefore those who were pregnant or very ill were removed outside, usually to their family's home.

Another interesting cultural element we find here is that, with the low level of medical knowledge, "healers" and priests would come to the house of the sick person and offer prayers or recite sutras to "heal" him or her. Many illnesses were thought to be caused by the influence of a malevolent spirit, so exorcists also often took part.

The story of the love between the Emperor and Kiritsubo has interesting overtones: it alludes to the story of the Chinese Emperor Xuanzong (685-762) of the Tang dynasty, who was in love with the imperial concubine Yang Guifei and in his obsession neglected affairs of state. This fomented a rebellion, which forced the emperor to flee for his life with Yang Guifei. During that flight, the imperial guards forced Xuanzong to put Yang Guifei to death. This tragic story became the object of one of the most popular poems in all Chinese literature: Changhenge or The Song of Unending Sorrow by Bai Juyi, a work that was also well-known in Heian Japan, and certainly to Murasaki Shikibu who had mastered Chinese and even taught the Empress the poetry of Bai Juyi). Although there is no rebellion and Lady Kiritsubo is not put to death, the infatuation of the Japanese emperor for a low-ranking concubine matches that of the Chinese emperor. By the way, the story of Yang Guifei was so popular in Japan that Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto even has a Kannon statue that is said to have been modeled on Yang Guifei ("Yokihi Kannon" - read my post on Sennyuji). In addition, Yang Guifei was the subject of a film by Mizoguchi Kenji in 1955; and the modern Japanese-style painter Uemura Shoen made a famous painting treating this subject.

"The Paulownia Pavilion" is the translation used by Tyler; Seidensticker has "Paulownia Court," which is just as fitting; Waley leaves the title in Japanese. Only Washburn is a bit cumbersome with his "The Lady of the Paulownia-Courtyard Chambers", although he does bring out the full meaning.

Chronology

This chapter describes the birth of Genji and his life through

age 12.

Position in the Genji

Kiritsubo, the first chapter of the Genji, is a sort of

introductory chapter, which sets up several important themes for the whole novel. As it is not well connected to the following chapter, Hahakigi, some scholars believe that it was added later, or even that a chapter between Kiritsubo and Hahakigi has been lost. However, it should be noted that the Genji

doesn't have the monocentric unity of the plot line of a modern novel. It is built up from parallel segments, or blocks, as the panels

of a folding screen. Murasaki Shikibu continually augmented and

amplified her narrative in a semi-circular motion, as Haruo Shirane says

(The Bridge of Dreams, p. 57). So I see no problem here; on the contrary, Kiritsubo is well connected to the overall theme of the novel, as it introduces Genji's illicit love affair with his stepmother, Fujitsubo.

Setting

Let's first look at the location where this chapter (and much of the Genji) takes place: the Imperial Palace in Kyoto (then called Heiankyo). That is not the present Kyoto Gosho Palace, a location on which the main palace has only stood since the 12th c. (the present buildings date from the mid-19th c.), but the Heian Palace, which stood much further west, centered on what is now Senbon Street, then called Suzaku Avenue. Suzaku Avenue stretched from the famous Rajomon Gate to the north, diving the capital (which was laid out on a Chinese-style checkerboard pattern) equally into a western and an eastern part. The palace occupied the north-central part of the city, from Ichijo Street in the north to Nijo street in the south and from Omiya street in the east to Nishi-Omiya street in the west. The palace and all its halls faced south, as was common in China. The Great Hall of State was located more or less in the center. The location is now indicated by a monument in a small park just north of the crossing between Senbon Street and Marutamachi Street.

[The monument indicating the location of the Heian-period

Great Hall of State]

The Heian Palace not only contained the living quarters for the imperial family (in the northern part, called dairi), but also all government ministries (in the southern part, called daidairi). A combination of the present Prime Ministers Residence with Kasumigaseki, so to speak. Like Gosho, the still existing old palace in Kyoto, it was secured by a mud-wall, and also by a moat. The central southern gate was called Suzaku Gate after the avenue onto which it opened. Close to this gate stood the Daigokuden or Great Hall of State, where all sorts of official ceremonies were held - the heart of governmental Japan in the Heian-period.

[Shishinden in the Kyoto Gosho palace, which had taken over the public function of the Daigokuden]

[The living quarters of the imperial family in the Heian palace. This block was surrounded by the administrative part of the palace, that extended to the south.]

Synopsis

The story that takes place in this palace, starts with a case of passionate love, of injudicious infatuation which will lead to tragedy. But before telling that tale, we have to make two more points. One is that polygyny (a form of plural marriage in which a man is allowed more than one wife i.e. a narrow form of polygamy) was practiced among the Japanese Heian aristocracy. This was also true for the Emperors, who besides the Empress, had several secondary consorts ("concubines"). This was not only for the practical purpose to produce more offspring, or out of sexual acquisitiveness, but also to make it possible for ranking aristocrats to present a daughter to the Emperor or Heir Apparent and thus share in the imperial prestige.The second point is that these imperial women were not equal, but like everyone in Heian society had to obey a strict hierarchy. (In fact, your birth decided your life in Heian times.) So below the single Empress (called Chugu) the Emperor would have several Consorts (Nyogo) and, lower still, a certain number of Intimates (Koi). An Empress was usually appointed from among the Consorts, but not all Consorts had a realistic hope of such a success, as it depended on family relations (i.e. a male family member with a powerful position at court). The Intimates could never become Empress, their birth rank was too low and they lacked sufficient political support. That is not to say that these ladies were really very low in status - while the Nyogo had fathers who were of ministerial rank, the fathers of the Koi were only just below that, as counselors or chunagon. But they obviously had much less power at court.

Talking about the power of the families of the imperial women, we also have to mention the fact that during much of the Heian period, the Fujiwara family managed to dominate Japanese politics through the strategy of marrying Fujiwara daughters to emperors. In that way the Fujiwara would gain influence over the next emperor who would, according to the family tradition of that time, be raised in the household of his mother's side and owe loyalty to his maternal family. Moreover, the father of the daughter who became empress, would monopolize the position of regent (sessho or kampaku). He would rule on behalf of the new emperor as long as that person was still a child or very young man – and when the emperor who never had any power himself, became an adult, he would be forced to abdicate and the next child-emperor would be installed under the tutelage of the same or another Fujiwara regent.

[Living quarters in the Kyoto Gosho palace]

Now the Genji starts with the situation that the Emperor can not control his amorous feelings for one of his concubines, the low-ranking Intimate (koi) Lady Kiritsubo, named after the pavilion where she lives, with a paulownia tree (kiri) in the small courtyard garden (tsubo). The fact that her rooms are farthest from the imperial chambers also indicates her low status. But that does not hold the Emperor back, on the contrary: deeply in love, he favors her above all his other wives, including his primary consort, Lady Kokiden, the daughter of the powerful Minister of the Right (she is the main Consort, but there is no official Empress at this time). This provokes the fierce jealousy of the other imperial concubines. Lady Kiritsubo is disadvantaged because of her low rank and lack of parental support (her father is already deceased), so she is constantly harassed by the other women. Her only support is the Emperor's personal devotion, but that is not enough. The humiliations she has to suffer make her waste away and finally trigger her premature death.

But the union between the Emperor and Lady Kiritsubo has by then already born fruit: three years before her death, a son has been born, a most handsome boy: our Genji. After the death of his wife, the Emperor dotes on the boy, who is nicknamed "Hikari," "the Shining." He is so handsome that he hardly seems of this world.

By the way, both such a birth and illness could not take place in the palace. Both birth and illness (or death) were considered as polluting and therefore those who were pregnant or very ill were removed outside, usually to their family's home.

Another interesting cultural element we find here is that, with the low level of medical knowledge, "healers" and priests would come to the house of the sick person and offer prayers or recite sutras to "heal" him or her. Many illnesses were thought to be caused by the influence of a malevolent spirit, so exorcists also often took part.

The story of the love between the Emperor and Kiritsubo has interesting overtones: it alludes to the story of the Chinese Emperor Xuanzong (685-762) of the Tang dynasty, who was in love with the imperial concubine Yang Guifei and in his obsession neglected affairs of state. This fomented a rebellion, which forced the emperor to flee for his life with Yang Guifei. During that flight, the imperial guards forced Xuanzong to put Yang Guifei to death. This tragic story became the object of one of the most popular poems in all Chinese literature: Changhenge or The Song of Unending Sorrow by Bai Juyi, a work that was also well-known in Heian Japan, and certainly to Murasaki Shikibu who had mastered Chinese and even taught the Empress the poetry of Bai Juyi). Although there is no rebellion and Lady Kiritsubo is not put to death, the infatuation of the Japanese emperor for a low-ranking concubine matches that of the Chinese emperor. By the way, the story of Yang Guifei was so popular in Japan that Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto even has a Kannon statue that is said to have been modeled on Yang Guifei ("Yokihi Kannon" - read my post on Sennyuji). In addition, Yang Guifei was the subject of a film by Mizoguchi Kenji in 1955; and the modern Japanese-style painter Uemura Shoen made a famous painting treating this subject.

Yokihi (Yang Guifei) by Uemura Shoen

In the Genji, there are not only allusions to the Yang Guifei tragedy, but courtiers explicitly make the comparison between the Japanese and the Chinese emperor's infatuation, and, after Kiritsubo has died, the emperor himself is found reading The Song of Unending Sorrow.

After the disastrous fate of Genji's mother, for whom the Emperor mourns like the Tang emperor did for Yang Guifei, the Emperor takes measures to protect the son of his beloved Lady Kiritsubo. Although he longs to appoint Genji Heir Apparent over his firstborn, the son of a Fujiwara consort, he knows that the court would never allow this. He therefore decides to remove Genji entirely from the imperial family by giving him a surname (the Japanese Emperors have none) and making him a commoner (tadabito). In that case, he will be able to serve later as senior government official. The Emperor is strengthened in this course by the advice of a Korean fortune-teller, who says that Genji has the appearance of an emperor, will attain a position equivalent to one, but cannot ascend the throne without causing disaster. The Emperor gives the boy the surname "Minamoto," which since the 9th century was the name for offspring from Emperors who were demoted to commoner status. The boy thus becomes a "Genji," that is a bearer of the Minamoto (Gen, another reading of the same character) name (ji). (Genji is often wrongly called "Prince" Genji, for that is exactly what he is not, as he has been removed from the imperial family roster).

This act is irreversible. Thus, Genji cannot ascend the throne in the future and the Emperor names Suzaku, Genji's half-brother and the son of Lady Kokiden (of Fujiwara stock) as Crown Prince. Suzaku is three years older than Genji. To further protect him and also help him along in later life, the Emperor arranges Genji's marriage to Aoi, the daughter of the Minister of the Left (and Genji's first cousin). This will ensure Genji of the powerful political support of his father-in-law, who can act as a counterbalance to the Kokiden faction (backed by the Fujiwara Minister of the Right). This marriage takes place when Genji is twelve (just after his coming of age ceremony) and Lady Aoi sixteen (a normal age for boys and girls to marry in Japan at that time in the aristocratic milieu). Needless to say that this political marriage is not a love relationship - Aoi is a very haughty woman who treats Genji as her little brother - at the time of the marriage he in fact must have looked like that to her! As was common in Heian times, Genji will now start living officially at the residence of his wife's family, although in reality he keeps spending much time in the palace, where he is allowed to continue using the Kiritsubo, his mother's pavilion.

Regarding age in traditional Japan, it is important to note that one's age was counted as "one" at birth and that at each New Year rather than at the individual birthday a year was added. So people are younger than the numbers show: we should at least subtract one year!

The Emperor finally finds consolation with another consort, called Fujitsubo ("Wisteria Pavilion"). She is the fourth daughter of a previous Emperor and thus an imperial princess, and is protected by her high status. She also uncannily resembles Lady Kiritsubo, Genji's dead mother. She enters the Emperor's service when she is sixteen and soon becomes his new favorite. But her resemblance to Genji's mother also attracts Genji's interest in her, an interest that is at first childish, but that later turns erotic (normally Genji would not have been allowed to look at her as women kept to their apartments and did not even show themselves to their nearest of kin, but here the situation is different as the Emperor himself has asked Fujitsubo to be like a mother to Genji; this however stops after Genji's coming of age ceremony at age 12). She becomes Genji's lifelong obsession and their secret, forbidden relation will drive much of the plot in the ensuing chapters. Genji dreams of marrying a woman like her...

Note that the forbidden love between Genji and Fujitsubo is never written up explicitly by Murasaki Shikibu, as that would probably have been too scandalous. But her hints are clear enough for readers to realize that this love must have been consumed also in the physical sense. By the way, during the 1930s and the war years with their emperor cult, even such hints (which could mean that the succession in the imperial house was not "unbroken") were taboo, so the first version of Tanizaki's Junichiro's Genji translation was heavily censored - reason for him to restore those passages in a new version he published just after the war.

By the way, this theme - the father who marries a woman who strongly resembles his deceased wife, the son who shifts the affection for his dead mother to the new one and finally falls in love with her, encouraged by the father - was used by Tanizaki Junichiro in his story The Bridge of Dreams (see my post about this novella). It is clear that Tanizaki's translation work was an inspiration for his creative work.

Genji-e

In pictorial representations of this chapter (so-called Genji-e), the following scenes are usually chosen: Lady Kiritsubo sending her final poem to the emperor; the emperor mourning the lady's absence and imminent death (both set in autumn); Genji's interview at age seven with a Korean physiognomist; and his coming of age ceremony (as in the above illustration). The episodes centering around Genji's clandestine love for Fujitsubo are never treated (JAANUS).Suggested readings of other literature besides this chapter in the Genji:

Tanizaki Junichiro, "The Bridge of Dreams," translated by Howard Hibbett in the collection Seven Japanese Tales (together with six other works by Tanizaki, including "A Portrait of Shunkin"), published in various editions by both Tuttle and Vintage.

Bai Pu, "Rain on the Wutong Tree" translated by by Stephen West and Wilt Idema in Monks, Bandits, Lovers and Immortals, Eleven Early Chinese Plays. Hackett 2010.

Bai Juyi, "The Song of Lasting Pain," translated by Stephen Owen in An Anthology of Chinese Literature (p. 441), Norton 1996.