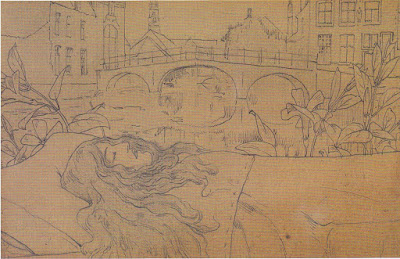

Bruges-la-Morte (1892) by Georges Rodenbach

A man is obsessed with the memory of his deceased wife and tries to mold a dancer, who uncannily resembles her, after his wife. "Bruges-La-Morte," by the Belgian Francophone author Georges Rodenbach (1855-98) is a melancholic novel about an obsessive love, a love both for a beautiful dead wife and a beautiful dead town. It is the novel of a poet, in which almost nothing happens, the reader is as it were incarnated in the lonely soul of the protagonist.

The main character in the novella is Hugues Viane, a middle-aged widower who, distraught at his wife's death several years before, has moved to Bruges. Bruges (in Flemish: Brugge), once the major trading city of Belgium (and today a bright tourist attraction), in the 19th century had become a dead town, dreaming of the past amid the mystic peace of its churches and cloisters, and for Hugues the desolate cityscape with its dark and stagnant canals symbolizes his own mood. He lives (or rather, sits brooding) among the relics of his beloved dead wife – her clothes, her letters and portraits, and most importantly, a length of her long blond hair kept almost religiously under a glass cover. In this way, he has erected an altar of sorrow and remembrance to his wife. Hugues has no occupation and rarely leaves the house. His only activity is a daily walk through the deserted and dusky streets of the old town, under the shadows of the ancient walls, listening to the old bells of the many churches, sometimes stepping into a church to see the sculptures on the ancient tombs (such as those of Charles the Bold and Mary of Burgundy), often longing himself for death, hoping to meet his beloved in a new life beyond the grave. It is a situation halfway between reality and dream. The memory of his wife monopolizes his every thought and deed. In fact, Hugues is in the thralls of a morbid and unwholesome cult.

Jane is only described from the outside, through Hugues, we don’t even get to hear her speech until the end of the novella. It may therefore seem that she rather too easily gives in to Hugues wishes: she becomes his kept mistress, and he rents a room in the suburbs for her where he pays daily visits; he also has her give up her profession. But in the 19th c. operatic dancing girls were virtually prostitutes and therefore it is highly probably that Jane would not be averse to a settlement where a gentleman would keep her in comfort. Rodenbach doesn't address this point – it was too sensitive for his bourgeois readers who anyhow understood the situation and valued discretion.

But of course, no two people are similar and Hugues soon discovers that the character of the new woman is very different from that of his deceased partner: for one thing, being who she is, she is far coarser. There is for example grotesque humor in the scene where Hugues persuades Jane to put on his dead wife’s dresses, and is mocked by her for their being out of date. His infatuation also has become the scandal of the town and sets numerous tongues wagging. Finally, his devoted servant Barbe also leaves him.

The final scene plays out in Hugues house. An annual religious procession, the Procession of the Holy Blood, will make the rounds of Bruges and also pass by Hugues windows, so Jane begs to be allowed to visit his house to watch the event. Jane comes for the first time to his house, and is interested in the portrait of his wife (“She looks like me”), without realizing what she is seeing. When finally she dares touch the precious coil of hair, just when the procession is passing, and jokingly winds it around her own neck, laughing scornfully, Hugues in a frenzy strangles her.

Almost nothing happens in this novel, that is focused on the description of a human being in a state of radical introspection. That makes the novel very modern – it is a mystery why it has been forgotten.

Something else that is very modern is that this is the first novel to incorporate dozens of black-and-white photographs (as for example contemporary author W.G. Sebald has done). The photos show mostly deserted streets and canals. Although they are an integral part of the novel, most modern editions leave them out – the English translation below has replaced them with new photos. Only the original images, however, have a truly haunting quality (they can be accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ca...).

Bruges-la-Morte enjoyed considerable success in its time. Rodenbach’s prose is beautiful and refined, it is a novel with a considerable literary quality. The novel led to something like a “Bruges cult”, as a place that was silent, melancholy and lost in time. This was not something appreciated by the inhabitants of Bruges, who were just then seeking new commercial life by the opening of the nearby port of Zeebrugge; after Rodenbach died, the citizens refused permission for a memorial statue in the town.

In 1920 the novel inspired Erich Korngold’s opera Die tote Stadt, which thanks to a Korngold revival in the 1990s, is again periodically staged in opera houses today. It has beautiful, elusive music and does full justice to the poetic qualities of the novel. It was the supreme masterwork of the then only 23-year old composer Erich Korngold (1897-1957), who wrote the libretto with his father, the music journalist Julius Korngold. The opera was a great hit, and it made a triumphal tour around the world – until the Nazis forbade it as Jewish music, while the immediate postwar generations were only interested in twelve-tone music. The lavish Straussian music brings out the tension between sexual desire and ideal aspiration, decay and death, and shifts from gloomy orchestral interludes to high-soaring song. The names were changed in the opera (Hugues is now Paul, Jane is Marietta and the deceased wife has become Marie) and the new character of a friend of Hugues is introduced. In the opera we see a sort of struggle between the dancer and the dead wife for the soul of Hugues/Paul, and most of the second and third tableau are presented as a dream vision – also the murder of the dancer takes place in this dream and after that, Paul wakes up cured – he will leave Bruges and stop with his morbid cult of the dead.

Bruges-la-Morte at Internet Archive (in French, there is no translation available in the public domain).