Modern Japanese Fiction by Year (6): The Decadent Postwar Years (1946-1950)

On August 15, 1945, a new historical period started in Japan with the surrender. The war had ended, but the whole country lay in ruins; almost all its major cities had been devastated by fire bombs and Japan had become the only country in the world to have suffered the atomic bomb. At least three million Japanese had died in the war and millions more were sick, wounded and malnourished. The economic infrastructure had been wiped out and basic governmental services were seriously disrupted. This was accompanied by widespread spiritual malaise and demoralization. The defeat brought feelings of guilt and humiliation, plus the bitter feeling that all these losses had been in vain. Veterans were treated with disdain and victims at home were treated with indifference. The sheer effort to survive took priority over everything.

The spiritual wreckage was symbolized by the flourishing of the black market (for a time the only viable outlet for goods), gangsterism and prostitution (much geared to serve the American conquerors). From colonizer, Japan had become colonized. In the face of such turmoil, many young people turned to a life of decadence and self-gratification, also as a release after two decades of repression. This pursuit of decadence was seen as another sign of the breakdown of order.

The Occupation authorities (the Occupation lasted from 1945 to 1952) imposed legal and economic reforms that fundamentally changed Japanese society and its value system. Big business, large-scale landholding and the family system were demolished, and democratic rights were introduced as was suffrage for women. People had to find new values and a new identity.

Remarkably, the chaos and deep changes in society, gave rise to a period of extraordinary creativity. The two decades following the end of the war were both culturally and economically, the most productive period in recent Japanese history. Despite some censorship enforced by the Occupation authorities (writings depicting the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were forbidden, as were graphic descriptions of food shortages or of involvement by American soldiers in black market activities), the overwhelming feeling was a sense of liberation and possibility.

The arts flourished and there was a great demand for new literature. The literature of the first few years after the war takes as its theme "the ruined country," like the German postwar "Trümmer-literatur." At the same time there was a leftist wave - Marxism was suddenly popular. Many leftists who had been imprisoned or forced to make public conversions reemerged and energized the literary scene with their ideas. Existentialism was also suddenly en vogue. Other writers brought iconoclastic perspectives to prominence.

With the revival of democracy, sex as a theme made a comeback with vengeance (and not only in the form of the nikutai bungaku or "literature of the flesh" described below). Previously, sex had blossomed as the subject of literature and entertainment during the "Taisho Democracy," from the 1910s to the 1920s, when ero-guro-nansensu (erotic, grotesque, nonsensical) became first popular. The subject next had forcibly been toned down in the 1930s and finally suppressed as taboo during the war years.

Japanese critics have made the following groupings among the major new writers of this period.

(1) In the first place the "Buraiha" ("Decadents" or "Ruffians"), consisting of Dazai Osamu, Sakaguchi Ango and Oda Sakunosuke (the Osaka writer introduced in the previous post), but also other writers as Ishikawa Jun, Ito Sei, Takami Jun and Dan Kazuo are often loosely included. The term "burai," which means "to transcend social norms," captures the writers' tendency to describe characters who overtly disregard traditional social custom. The main characters in their works are anti-heroes that are dissolute and aimless. They criticized prewar Japanese literature as well as the American social values that were introduced into Japanese society with the Occupation. In private many of these writers also embodied the decadence they portrayed in their fiction (this is very much true for Dazai and Oda, but not for Ishikawa and others). They spent time in bars, took narcotic drugs and had extramarital relationships. They were in all senses of the word "decadent." By the way, another name for the group was Shin Gesaku-ha, "New Burlesque Group" (referencing Edo-period gesaku fiction). Buraiha was not a conscious group with a program. Rather than a literary movement, it was a reflection of the historical circumstances in which new values had to be established. Most popular was Dazai Osamu, who followed the Shishosetsu tradition in which the author makes explicit use of his personal experiences. At the same time Dazai went against tradition by using a technique of metafiction he learned from Gide - for example by intruding in his story and exposing the fact that it is fictional and not a true exposition of his life. He was a true "burai," a violator of conventions. A seminal essay was Sakaguchi Ango's "On Decadence" (Darakuron). This trend was short-lived as Dazai committed suicide in 1947, Oda died from an illness in the same year and Sakaguchi died suddenly in 1955.

(2) Another group, the so-called "First Generation of Postwar Writers," which included Noma Hiroshi, Takeda Taijun, Fukunaga Takehiko, Shiina Rinzo, Umezaki Haruo, Nakamura Shinichiro and (the critic) Kato Shuichi, and viewed the war from a political and philosophical point of view. Many of them were Marxists, who could again write after having spent time in prison during the war, or after having temporarily been forced to revoke their leftist views. They started writing in 1946 and 1947, and focused on the plight of human beings in extreme conditions. They often linked literature with leftist politics, and there is an existentialist trend (Sartre became very popular in Japan immediately after WWII). They also reject the realist novel and the Shishosetsu. The most typical writer was Noma Hiroshi, with a novella as Dark Pictures, set in the milieu of leftist students in Kyoto just before the war.

(3) "The Second Generation of Postwar Writers" is a loose designation for writers who appeared on the postwar literary scene between 1948 and 1949. They were Mishima Yukio, Abe Kobo, Ooka Shohei, Shimao Toshio and others. Like the first generation, these authors were marked by their wartime experiences which initially dominate their fiction. In contrast to the leftists of the First Generation, who generally applauded the postwar changes in Japan, Mishima took a negative attitude from a conservative stance and believed that more had been lost than gained. He was an all-round writer who used a difficult Baroque style and wrote in all genres, from essays to stories, from novels to theater. Abe was politically to the left and is known for his dystopian novels written in a scientific style. Like Mishima, he gained a strong international audience. Due to his wartime experience as a soldier in the Philippines and after that as a POW, Oka became the prime writer about the war from a humanistic viewpoint with his novel Fires on the Plain.

The above listings don't cover all new writers in this fecund period. One other new writer from 1949 was the popular Inoue Yasushi, who wrote contemporary fiction, autobiographical novels as well as historical novels. Inoue was not included in any one of the postwar generations as he had already published his first fiction in the 1930s - although that was a one-off event as he had turned towards journalism for many years. But born in 1907 he was of an older generation than most other writers who started writing after the war.

1946

The Showa Emperor renounces his divinity in a New Year’s address to the Japanese people (ningen sengen) and reminds them that in the Charter Oath the Meiji Emperor had already adopted democracy, which therefore was not something outlandish. A new constitution is promulgated, which goes into effect in 1947.

Occupation purge of wartime leaders.

The Nankai Earthquake strikes Wakayama, killing 1,443.

(1) Stories by Ishikawa Jun.

Ishikawa Jun has already been introduced in the previous post. As we saw above, he was included in the Buraiha, but only because of his fierce opposition to authority, not because he led a decadent life. In fact, the Modernist Ishikawa held himself aloof from the Shishosetsu style of Dazai and others, and never wrote about his personal life. His works are pure fiction. In the years after the war he concentrated on stories and novellas, but later he switched to writing long novels with a fantastic content. He was also deeply interested in Edo-period gesaku fiction and kyoka poetry. The following three stories are among his most representative.

- "Meigetsushu" (Moon Gems)

In "Moon Gems," the narrator, living in the Yamanote section of Tokyo, has chosen withdrawal into the imagination as a way to cope with the war which is in its last year. This is symbolized by his practicing to ride a bicycle on an empty plot near his house. A poor, crippled girl acts as his teacher. The story also features the hermit-poet Mr Guka, which is in fact a portrait of Nagai Kafu (just like Kafu, during the aerial bombardments Guka looses his house and book collection, and just like Kafu - and Ishikawa - he practiced a sort of "inner emigration" during the war, leading a hermit-like life out of the public eye; that intellectuals would withdraw from public life and become hermits in times the government was morally wrong, was already a form of protest in Chinese culture). The story has been influenced by the kyoka poetry of the Edo period, which Ishikawa studied during the war years.

- "Ogon no densetsu" (The Legend of Gold)

"The Legend of Gold" is a serio-comic series of vignettes of Japan just after the war. An American soldier is portrayed as purveyor of black-market cigarettes and chocolates to his Japanese girlfriend, which led to the story being banished by the Occupation authorities - and therefore becoming famous. The protagonist wants his watch repaired, buy a new hat and he also is seeking for his girlfriend - watch and hat are symbols of the restoration of time and dignity after the ignominy of the war years. Even though the protagonist looses his girlfriend to a conquering soldier (a symbol for the surrender of Japan to the Americans), he remains proud.

- "Yakeato no Iesu" (The Jesus of the Ruins)

"The Jesus of the Ruins" is a story set at the large black market next to Ueno Station, where many little shops have been erected on the site of burned-out buildings. A young boy with a face covered in boils upsets the black market by his impish or perhaps even demonic activities, fighting for food. In the end in a struggle with the narrator, he steals his bundle, but the narrator also experiences a moment of epiphany when gazing into the boy's face - as if seeing Jesus. This, because the boy has returned to an elemental state that is free of tradition.

[(tr. William J. Tyler in The Legend of Gold and Other Stories by Ishikawa Jun, Hawaii U.P.]

Ishikawa is recognized as not only a superb craftsman but also a thoroughgoing methodologist of the novel. At the same time that he belongs to the modernist tradition within 20th-century fiction, he can also be seen as part of the "literati" (bunjin) tradition that originates in the poets and Bunjinga painters of the Edo period and that descends through Mori Ogai and Nagai Kafu.

(2) Short stories by Sakaguchi Ango

Sakaguchi Ango exaggerated the ghastly environment of the ruined metropolis around him to produce a nihilistic portrait of a society gone mad and values turned upside-down. His blackly sarcastic wit epitomized the feelings of many in the postwar period.

- "Hakuchi" ("The Idiot")

A famous story based on the author's experience of living in Tokyo during the worst period of fire bombings in March 1945 - it has been called one of the best descriptions of urban aerial bombardment in all modern literature. Set in densely-populated, working class Tokyo neighborhood. The protagonist's neighbors are all described as cruel, venal, mean, and incest, prostitution and suicides abound. One night he finds the mentally retarded wife of next door crouching in his cupboard. She has apparently been chased away and he decides to take care of her. In their desperate efforts to survive, the protagonist comes to the realization of shared humanity with the woman. The story reveals the importance of people’s self-salvation (both physical and spiritual) during wartime. Shows wartime humanity liberated from the yoke of moral indoctrination. This short story can be considered as an embodiment of Ango's "Daraku-ron."

[tr. by George Saito in Modern Japanese Stories, ed. Ivan Morris]

- "Senso to hitori no onna" ("One woman and the War")

Set in the last days of the Pacific War, as the population awaits an imminent Allied invasion of the Japanese mainland and what they believe will be an accompanying campaign of murder, rape and pillaging. The story is told by a former prostitute turned bar owner. Depicts a sexuality devoid of all sentimentality.

[tr. by Lane Dunlop in Autumn Wind and Other Stories]

- "Sakura no mori no mankai no shita" ("In the forest, under cherries in full bloom," 1947)

A combination of folk tale and horror story, this is in fact a bitter parody of the Japanese fetish for cherry blossoms (as Susan Napier writes in The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature, p. 197), alleging that far from beautiful or lyrical, cherry blossoms are ominous and sinister and connected to madness. Filmed in 1975 by Shinoda Masahiro.

[tr. by Jay Rubin in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories]

Born in the city of Niigata, Sakaguchi Ango (Sakaguchi Heigo, 1906-55) studied Indian Philosophy at Toyo University and graduated in 1930. He was the son of a high-level local administrator. Although he wrote his first stories in the 1930s, Sakaguchi is primarily associated with the postwar period. He is known for his black, sarcastic wit. His best stories are set among the prostration and confusion of defeat, among the ruins, so to speak. Like Dazai, he is essentially a youthful writer, who died fairly young, and like Dazai he is counted among the writers of the Buraiha or "Decadent School," a group of dissolute writers who expressed their aimlessness and identity crisis in post-WWII Japan. In 1946 he wrote his most famous essay, titled “Darakuron” (“On Decadence”). He urged the Japanese to abandon the discredited, restrictive customs of the past (and the false morality of the wartime period) and seek their salvation in a rediscovery of the basics of human nature. Reveals his penchant for iconoclasm and irreverence for things traditional. In 1947, Ango Sakaguchi wrote an ironical murder mystery, Furenzoku satsujin jiken ("The Non-serial Murder Incident"), for which he received the Mystery Writers of Japan Award. His immense popularity in the immediate postwar years led to pressure from the public and publishers to write more and more and caused a heavy reliance on alcohol and drugs, until a breakdown in 1949, after which he took things easier.

(3) Three stories by Noma Hiroshi

- Kurai e ("Dark Pictures")

The "dark pictures" of the title refer to several paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, which the protagonist and his friends have viewed together in an art book. The surreal miseries depicted in Brueghel's work represent the torments of the human condition, and especially of warfare. The story is set at Kyoto University, which in the late 1930s was a center of leftist thought and opposition to militarism. The protagonist is a young man who (like Noma himself) sympathizes with communist ideas and is friendly with members of secret left wing groups without actually being completely won over to communism. He visits a group of three friends who even after the outbreak of the China Incident in the summer of 1937 continue to resist militarism - and would later die in military prison. The protagonist is tormented by self-doubt and sexual anxiety. The bleak novella is written in an opaque and tortured style, with innovative sections of stream-of-consciousness prose. It was called "the first voice of postwar literature" by critics.

- "Hokai kankaku" ("The Feeling of Disintegration")

In contrast to Dark Pictures, which is political in intent and therefore contains some dated discussions, the other two early stories by Noma Hiroshi are purely Existentialist. The main characters are young men who have lived through the war and emerged with both physical and psychological scars. At the same time they are plagued by universal anxieties about sexual desires and their place in the world. In "Hokai kankaku" a student lodging in the same house as the protagonist, commits suicide and the landlady asks our hero to wait with the body, dangling from the ceiling, until she is back with the police. The protagonist meditates on death and suicide, thinking about the war, and frets because he will miss his date with his girlfriend, who probably will not wait for him if he is late.

- "Kao no naka no akai tsuki" ("A Red Moon in Her Face")

While he was at the front, the protagonist's girlfriend, whom he always treated with contempt, had died in the war back home. He feels doubly guilty because during a forced march he has abandoned a comrade, who didn't have the strength to go on, to his fate. Back in Japan after the war, he meets a young war widow he finds attractive and feels sorry for, but he is powerless to act on his feelings: he is unable to enter into another relationship.

[All three stories tr. James Raeside in "Dark Pictures" and other stories by Noma Hiroshi, University of Michigan, 2000]

Noma Hiroshi (1915-1991) was born in Kobe and studied French literature at Kyoto University with a particular interest in French Symbolist poetry. Noma was also interested in Joyce, Proust and Gide. He became active in the underground Marxist student movement. During World War II he was drafted and sent to the Philippines and northern China but later was imprisoned (1943–44), on charges of subversive thought. After the war, Noma attracted attention with the above novellas. His later novel Shinku chitai ("Zone of Emptiness", 1952) is a compelling account of corruption and brutality in the army, set in a military barracks in Osaka in the later stages of the Pacific War - this became his most popular work and was filmed by Yamamoto Satsuo. It is also written in more straightforward prose. Noma's magnum opus was Seinen no wa ("Ring of Youth"), a multi-volume work begun in 1949 and only completed in 1971, which builds on Noma's experience with burakumin and the buraku liberation movement.

(4) Honjin Satsujin Jiken ("The Honjin Murders") by Yokomizo Seishi

The first novel in the Kindaichi Kosuke series, about a murder in a locked room in a Japanese mansion surrounded by thick snow (a "honjin" is an Edo period inn for government officials, generally located in post towns). Filmed in 1976 by Takabayashi Yoichi.

[tr. Louise Heal Kawai, Pushkin Pegasus 2020]

Yokomizo Seishi (1902-1981) was born in Kobe and studied pharmacy at Osaka University. But as he was fond of detective stories, instead of taking over the family drug store, he traveled to Tokyo where he met Edogawa Ranpo and managed to get a job at a publishing company. Yokomizo Seishi's fame came in the immediate postwar years, when he wrote several puzzle mysteries characterized by theatrical, "dressed-up" murders (mitate satsujin), in rural "Old-Japan" settings. Yokomizo had used the war years to read up on orthodox English and American crime fiction - Van Dine's The Bishop Murders has been mentioned as the possible inspiration for Yokomizo's metaphorical murders. Such impossible murders solved by genius-like detectives had been quite common in the "Golden Age" in England and America, but were new for Japan and took the market by storm. Popular titles by Yokomizo are Gokumonto ("Gokumon Island," 1947) and Inugamike no ichizoku ("The Inugami Clan," 1950). Although Yokomizo lost his prime position when Matsumoto Seicho arrived in the second half of the fifties, his major novels have retained their popularity: his Gokumonto has been No 1 on both Tozai Mystery Best 100 lists (of 1985 and 2012). That was also thanks to the boost given by the films made by Ichikawa Kon in the 1970s and 1980s.

1947

Constitution of Japan goes into effect. First postwar elections for House of Councilors and House of Representatives. Supreme Court of Japan established.

Death of Koda Rohan (1867-1947). Death of Yokomitsu Riichi (1898-1947). Death of Oda Sakunosuke (1913-1947).

(1) Bestselling novel and stories by Dazai Osamu

- Shayo ("The Setting Sun") by Dazai Osamu became an immediate bestseller, making the author a celebrity.

Set amid the ruins of postwar Japan, Shayo describes the relationships between Kazuko, a divorced woman approaching 30; her decadent brother Naoji; and a novelist, Uehara. Bankrupt in the economic chaos of the time, Kazuko and her mother, an elderly and dying member of the aristocracy, are forced to surrender their home in Tokyo and move to the countryside of Izu. Naoji, recently released from the army, where he became addicted to drugs, suddenly appears, compounding the difficulties of life for both women. In the company of Uehara, Naoji leads a life of dissipation and alcoholism. Then their mother dies, and Naoji, who believes he has inherited her aristocratic nature, commits suicide. Kazuko, pregnant from an affair with Uehara (whose child she consciously wanted) remains to carry out a moral revolution against the background of the destruction that surrounds her. An apt metaphor for Japan's calamitous defeat after marching for a decade under the sign of the rising sun. Young people saw Dazai as the voice of their generation and fans thronged his house. The literary establishment, however, considered Dazai as frivolous and insignificant. But Dazai's personal life was in shambles. Besides a wife and three children at home, he had a baby daughter by a fan, Ota Shizuko, who had approached him as she wanted to become a writer; all the same, he spent most of his time with his new lover / secretary, the young war widow Yamazaki Tomie. Dazai had met Ota Shizuko in 1941, and while in Aomori, carried on an increasingly passionate correspondence with her. In early 1947 Dazai stayed for almost a week at her house and borrowed the diary he had encouraged her to keep - this became a partial inspiration for The Setting Sun.

P.S. Mishima Yukio, who did have a few drops of aristocratic blood, and who strongly disliked Dazai and his writings, has pointed out Dazai's insufficient knowledge of the speech and daily customs of aristocratic society as manifested in The Setting Sun. He considered Dazai as a "rustic." (Inose and Sato, Persona, p. 163)

[Tr. Donald Keene]

- "Merii kurisumasu" ("Merry Christmas" ) was the first story Dazai wrote after returning from Aomori to Mitaka in Tokyo in late 1946. The narrator, back in Tokyo after the war, happens to meet Shizueko, the daughter of an aristocratic woman he in the past had felt real affection for. The reason for his love for the mother were: she was a stickler for cleanliness, she was not infatuated with him, she was sensitive to his feelings and she always had liquor in her apartment. The narrator asks Shizueko to take him to her mother, but when they reach the apartment, it finally appears that the mother has died some time ago in the air raids, something the daughter was incapable of telling him. They then have a meal of broiled eel and sake for three persons to commemorate the mother. The "Merry Christmas" is called out by a drunken customer at the eel stand when he sees an American soldier passing.

[tr. Ralph F. McCarthy in Self Portraits; also in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories]

- "Bion No Tsuma" ("Villon's Wife") is a moving evocation of postwar Japan. The wife of a decadent and often drunken poet starts working as a waitress in a bar to repay the money her husband has stolen there. She comes to enjoy the work even though she is struck by a series of disasters and even raped by a customer. The title is based on a misunderstanding from the side of Dazai: he wrongly believed that the French Medieval poet Villon was just such a tormented soul as the poet in his story (and he himself).

[Tr. Donald Keene in Modern Japanese Literature, An Anthology]

(2) Existentialist and violent stories by Takeda Taijun

- Mamushi no sue ("This Outcast Generation," lit. "Brood of Vipers," 1947), about the Japanese who lived in Shanghai following the defeat. This existentialist novella is set in Shanghai, in the chaotic period just after the capitulation of Japan. The Japanese remaining there, first the victors and suppressors, now have been forced into the shameful role of losers. The nihilistic protagonist, Sugi, earns his wages by writing letters in Chinese for his countrymen. He is only an intermediary, the problems of others are of no concern to him. This changes when he gets involved with the fate of a certain woman and her sick husband. The woman has been compelled into an affair by a Japanese officer, Karashima, after he has first sent the husband - his subordinate - away. Also after the husband has returned home very ill and is about to die, this forced relation is continued by Karashima. Sugi (who has hidden tender feelings for the woman) decides to give up his passive attitude and kill Karashima, who for him is the personification of evil. Although the surprising end of the story doesn't give Sugi the expected triumphant feeling of successful revenge, it does provide him with a better awareness of the human condition. The title, by the way, is based on Matthew 23:33: "You snakes! You brood of vipers! How will you escape being condemned to hell?"

[Tr. Sanford Goldstein and Yusaburo Shibuya in This Outcast Generation and Luminous Moss]

- "Igyo no mono" ("The Misshapen Ones," 1950)

A powerful semi-autobiographical account of the uncertain novitiate of a sex-obsessed young priest. A young man who as a socialist would like to create Heaven on earth rather than wait for the next life, enters the seminary to become a priest for the sole reason that his father is a priest, too, and that he will inherit the rich family temple. He battles with his sensuality, but cannot even look at a girl, because to the people of the world, the monks are generally considered as the eccentrics, the misshapen ones. They are a kind of aliens who have connections with the other world and are only necessary when someone dies. But the protagonist loves this world...

[tr. Edward Seidensticker in The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature Volume Two]

- Runinto nite ("On the Island of the Exiles," 1953)

Set on Hachijo-kojima, a small volcanic island approximately 287 kilometers south of Tokyo, in the northern Izu archipelago. Although possessing beautiful cliffs and abundant sea life, life on the island was harsh and in 1968 it was deserted by its total population. Since the Middle Ages, the island had been a place of exile for dangerous convicts - the strong currents made escape impossible. In the time of the story, the early 1950s, there are still some convicts as forced laborers on the island, In fact, 15 years ago, the protagonist was also such a forced laborer and he has come back to the small island, split by internal strife, to take revenge, as a latter-day Count of Monte Christo...

[No English translation]

Takeda Taijun (1912-76) was born in Tokyo as the son of a Buddhist priest and studied Chinese at Tokyo University. His major literary influences came thus from China rather than from Europe, which was relatively unusual in the postwar period. Takeda is also known for his critical biography of the Chinese Han-dynasty historian Sima Qian. He had a wide knowledge of Buddhism. In the 1930s he was engaged in left-wing activities, but from 1937 to 1939 he was drafted in the army and served in China. Immediately after the war he worked as a translator in Shanghai, like the protagonist from Mamushi no sue. Takeda's many novels and stories are infused with a sense of guilt concerning his participation in the war against China, a betrayal of his original political beliefs. He also demonstrates an almost morbid interest in the dark sides of human nature and there is much violence in his stories. It is regrettable that so little of his work has been translated.

(3) Nikutai no Mon ("Gate of Flesh") by Tamura Taijiro (1911-83) depicts the activities of a group of prostitutes ("panpan girls") living in a ruined building in central Tokyo. This sexy novel, a famous example of what was called "the literature of the flesh," created a sensation and was five times filmed. The best version is that by Suzuki Seijun from 1964.

[No English translation]

"Nikutai bungaku" ("Literature of the Flesh" or "Carnal Literature") meant three things. In the first place it was an ideological designation, contrasting the wartime "kokutai" ("body of state"), a term for the state under the emperor system, as abstract concept that had no reality, with what had been discovered as the only reality during that same war: the human body. After all, that body needed food, shelter and sex, and in a time of danger and need that practical reality was more important than any political philosophy. In the second place the term came to be used for the work of literary authors who in the years after the war gave a central position to the body. These were especially Noma Hiroshi and Sakaguchi Ango, who stressed the (often carnal) desires of the body. And finally it was a type of pulpish literature (also called "kasutori" literature after the cheap shochu that after the war was made from the discarded dregs of other beverages) in which male writers during the Occupation portrayed female characters as literally embodying the fate of Japan, particularly through narratives that show them as prostituting themselves to American GIs. The use of the bodies of Japanese women then becomes a trope for expressing the indignity that men felt as a result of defeat and Occupation. Although these pulp novels offered men a means of escape from the sense of emasculation and inadequacy during the American Occupation, it was basically a misogynistic literature that projected all kinds of negative qualities onto Japanese women.

1948

November 12: International Military Tribunal for the Far East hands down death sentences for 7 war criminals and imprisonment for 18 others.

Fukui Earthquake, one of the heaviest of the 20th c. in Japan (3,769 deadly victims).

Death of Dazai Osamu (1909-1948).

(1) Ningen Shikkaku ("No Longer Human"), the last finished novel by Dazai Osamu.

The chronicle of a young man's progressive decline to self-destruction until he feels no longer human is in fact a reworking of material already used in Dazai's stories "Omoide" and "Tokyo Hyakkei" (see under 1939 in my previous post). The novel consists mainly of notes written by Oba Yozo, a young man born into a wealthy family in northern Japan (like Dazai himself). Oba grows up with a terror and distrust of people and is plagued by a sense of alienation and difference. His inability to understand the emotions of others, leaves him in a state of desolation. Sent to Tokyo for his education, he tries to hide his fears, and placate people around him by acting like a clown. When, after an unsuccessful attempt at double suicide, his family cuts him off, he becomes the kept man of one woman after another. Oba knows he is hurtling headlong towards self-destruction, especially as he also gets addicted to morphine, but is unable to change the course of his life. Eventually Oba returns as a broken man to his hometown, feeling he is unfit to be called "human." Written in the style of the Shishosetsu, the novel is told in a brutally honest manner, mostly devoid of sentimentality. Dazai finished writing Ningen shikkaku in mid-May 1948, while staying with his lover, the young war widow Yamazaki Tomie. On June 13, 1948 Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal near his house (the narrow Tamagawa Aqueduct had a swift current in the rainy season and therefore was a popular place for suicide). Their bodies were not discovered until June 19, which ironically happened to be Dazai's 39th birthday. At the time of his death he was writing a novelette with the title "Goodbye," which remained unfinished (it is in fact about a man who rids himself of his many entangling relationships with women, including a war widow).

[tr. Donald Keene]

(2) "Bangiku" ("Late Chrysanthemum") by Hayashi Fumiko.

Hayashi Fumiko was already introduced in my previous post as the daughter of a traveling peddler who worked nights in a factory to put herself through high school and finally became one of Japan's most read novelists. This story - arguably her best - offers a vivid portrait of an aging geisha, Kin, who reluctantly receives a former lover. Kin has come well through the deprivations of the war, having some money in real estate. But her previous lover - now married - has become seedy and just wants to borrow money from her. He ogles the maid and gets drunk, insisting to stay over. When he goes to the toilet, Kin quickly burns an old photo in which he still looked youthful. This is the end for her. Filmed by Naruse in 1954.

[Translated by Jane Dunlop in A Late Chrysanthemum].

(3) Tanizaki finishes publishing Sasameyuki, the greatest cosmopolitan novel since the Meiji-period. Serialization had begun in 1943 (see my previous post for a discussion of the novel), but publication was halted by the censor after two installments. After the conclusion of World War II, the novel was published in three parts: Book 1 in 1946, Book 2 in 1947, and Book 3 in 1948.

1949

Three unsolved incidents happen around the JNR (Japanese National Railways), which is then locked in a labor conflict: the Shimoyama Incident (disappearance and death of the first president of JNR), the Mitaka Incident (an unmanned train driving into Mitaka Station and killing 6 people) and the Matsukawa Incident (the derailment of a JNR train in Fukushima killing three crew members). The union and Communist Party were both blamed for sabotage. The first two incidents were used in the novel Kuroshio by Inoue Yasushi (see below).

The Yomiuri Prize for Literature is established by the Yomiuri Shinbun Company to help form a "strong cultural nation." Major winners over the years are for example Ooka Shohei (Fires on the Plain), Mishima Yukio (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion), Abe Kobo (The Woman in the Dunes) and Oe Kenzaburo (The Rain Tree).

(1) A breakthrough novel by Mishima Yukio is published: Kamen no Kokuhaku ("Confessions of a Mask").

Not his first published work, but Mishima's breakthrough novel, written at age 24, about the sexual awakening of the narrator, a boy from a upper-class family, who hides behind a mask in order to fit into society. This novel also introduced Mishima's masochistic fantasies, as well as his preoccupation with the beauty and decline of the (male) body, themes which recur in his later work as well. In fact the novel is separated into two different narratives: the first two chapters contain the story of the narrator's growing fascination with persons of his own gender, as well as with sadomasochism; the last two chapters are about the narrator's failed relation with a young woman who attracts him (autobiographically based on Mishima's infatuation with Kuniko, the sister of his friend Mitani). The protagonist's loneliness was felt to epitomize the alienation experienced by young people after WWII who could not adept successfully to the unsettled conditions of their society. The title mocks the pretension to unadorned confession characteristic of the Shishosetsu genre and hints at an important aspect of Mishima's aesthetics: the emphasis on the beauty of artifice.

[tr. Meredith Weatherby]

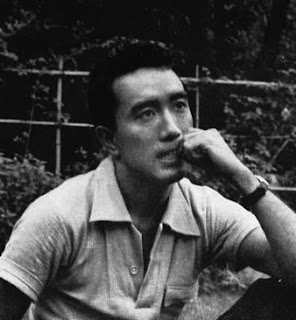

Mishima Yukio (Hiraoka Kimitake, 1925-1970) was one the most brilliant of twentieth century Japanese authors, and also one of the most problematical. Highly talented, Mishima started writing at the end of the war and at high speed produced many acclaimed novels, short stories and literary essays, as well as modern plays for the Noh and Kabuki theaters. Other famous works are, for example, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), After the Banquet (1960), The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea (1963), Death in Midsummer (1963), and the Sea of Fertility tetralogy (1965-70). Mishima was a dandy and liked to pose for staged photos or play in films. He had several friends in the American community in Tokyo and spoke excellent English. In the late 1960s, Mishima was several times nominated for the Nobel Prize, but he was passed over due to the extreme right-wing ideas and activities he had developed by that time (including a private militia of 100 radical youths). In 1968, the Nobel Prize was awarded to Mishima's mentor, Kawabata Yasunari. Mishima died on November 25, 1970, through ritual suicide, after a failed attack with his militia on the head-quarters of the Self-Defense forces in Tokyo. This dramatic suicide shocked both his readers in Japan and abroad.

[Biography: Persona, A Biography of Yukio Mishima, by Inose Naoki and Sato Hiroaki; Study: Escape from the Wasteland, by Susan J. Napier; Deadly Dialectics by Roy Starrs; Mishima: a Biography by John Nathan; and The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima by Henry Scott Stokes]

(2) Inoue Yasushi appears on the literary stage with a great variety of fiction.

- Ryoju ("The Hunting Gun")

This novella follows the consequences of a tragic love affair. Told from the viewpoints of three different women, this is a story of the psychological impact of illicit love. Three lovers give their view of the hunter and reconstitute his multidimensional nature. First viewed through the eyes of Shoko, who learns of the affair through reading her mother's diary, then through the eyes of Midori, who had long known about the affair of her husband with Saiko, and finally through the eyes of Saiko herself. The Hunting Gun is like Akutagawa's “In a Grove,” a love story with multiple narrators where each narrative reshapes the reader's understanding of the rest.

[tr. Michael Emmerich, Pushkin Press]

- Togyu ("Bullfight")

Inoue found the subject for Bullfight in the chaotic postwar Japanese society. It depicts the frenzied activities of an enterprising newspaper executive, Tsugami, who is promoting a bullfight in Osaka, the success or failure of which will determine the fate of his firm. For months this great gamble consumes him, making him as wary and combative as if he was in a ring himself. And, as he becomes ever more distant, his lover Sakiko is unsure if she would like to see him succeed or be destroyed. Established Inoue Yasushi as one of Japan's most acclaimed authors and earned the Akutagawa prize in 1949. (Note that this concerns a traditional, Japanese-style bullfight, i.e. between bull and bull and not with a matador. In Japanese bullfights, usually no blood flows).

[tr. Michael Emmerich, Pushkin Press]

- Kuroshio ("The Black Tide," 1950)

This short novel, which inexplicably has not been translated into English, forms as it were a trilogy with the above two novellas. Like Bull Fight, it is set in the world of newspaper reporters Inoue himself worked in for more than a decade. Moreover, by using a real life event as part of the plot, Inoue initiated the genre of "novels about contemporary events," that became quite popular and was followed for example Mishima Yukio (starting with The Blue Age from 1950, and including The Temple of the Golden Pavilion and After the Banquet). The president of Japan National Railways, who has just effected a massive lay-off of 100,000 and is struggling with the unions, is found dismembered on a railway embankment. Was it murder? Or suicide? Inoue's protagonist is the editor Hayami, who maintains a neutral stance in his paper, while the other newspapers jump on the case and portray it as a murder sensation. Hayami has strong reasons to avoid speculation: a few years ago, his wife died in a double suicide with a popular singer and Hayami was shocked by the groundless speculations in the media at that time. He felt it destroyed the dignity of those who died and made him loose sovereignty over his own life. While his own job as a newspaperman is only "black and white," Hayami has befriended his former drawing teacher, who now does research into old methods to dye fabric, a world of subtle colors. There is also the possibility of a renewed marriage with Keiko, the daughter of this teacher. A sharp novel about a chaotic time, emphasizing the importance of truthfulness.

[German tr. by Otto Putz]

- "Hira no shakunage" ("The Rhododendrons (of Mt Hira)," 1950)

Professor Miike Shuntaro, now 78, has all his life studied the circulatory system of the Japanese. As it happens, at each crisis in his life he spends time in an inn in Katada (Shiga Pref.) from where he imagines the white rhododendrons of nearby Mt Hira which he knows from a photo in a magazine. He is a typical selfish scholar with little empathy for other human beings, including his closest family and one of Inoue's typical postwar lonely human beings. The first time he visits Katada is when he is 25 and harbors thoughts of suicide – the cry of a bird on Lake Biwa, full of vitality, makes him decide to continue living. The next time he is in his early fifties. His eldest son has committed double suicide with a girl he has made pregnant by jumping into the lake, after being ostracized by his stern father. The third time is during the dark war years and the last time in the postwar years when Miike has run away from his family after a quarrel about money. The selfish musings of an old man, who has completely and habitually neglected his family for his “research,” which will never be finished or even published.

[tr. Edward Seidensticker in Lou-lan and Other Stories]

- Aru gisakusha no shogai ("Life of a Counterfeiter," 1951)

A writer is commissioned to write the biography of a famous painter but becomes fascinated by his shadow, a man who produced forgeries of the artist's work - the master forger lives in obscurity and disappointment, oppressed by the reality of the artist whose work he copies.

[tr. Michael Emmerich, Pushkin Press]

Inoue Yasushi (1907-1991) was a prolific writer active in many genres: short stories, novels both modern and historical, essays, travel writing and poetry. He was born in Asahikawa, Hokkaido and spent most of his youth living with his grandmother on the Izu Peninsula. He studied art history at Kyoto University, after which he joined the Mainichi Shinbun as a newspaperman for the next dozen years. Inoue was one of Japan's most prolific writers. His work falls into several categories. Firstly, Inoue was one of Japan's finest historical novelists. Works such as Lou-lan, Tun-huang and The Roof Tile of Tempyo established his reputation and among his popular successes are the fictionalized biographies of Confucius and Genghis Khan, as well as the 1953 Furin Kazan. Secondly, contemporary love stories with an existentialist twist, preeminently The Hunting Gun, admired for its complex female characters. Thirdly, novels addressing the social and political aspects of postwar Japanese society, often with reporter protagonists much like Inoue himself before his retirement. Examples are The Bull Fight, Black Tide and The Ice Wall (except The Bull Fight, these last two books have not been translated into English, although there are German versions). Lastly, there are Inoue’s (semi-) autobiographical writings, such as a novel of childhood, Shirobamba, and a moving nonfictional account of his mother’s descent into old age and dementia, Chronicle of My Mother.

(3) Kawabata Yasunari starts serializing two of his most important novels.

- Senbazuru ("Thousand Cranes," 1949-52) is a novel of romantic entanglement set against the ancient art of tea.

The protagonist Kikuji is drawn to Mrs Ota, the mistress of his deceased father, and after her suicide, to her daughter Fujiko, who flees from him. The “thousand cranes” of the title (a symbol of long life) occur as the pattern on a furoshiki another young woman Kikuji meets at the tea ceremony, Yukiko, carries. She is the only clean and healthy person in the narrative, but because Kikuji hesitates too long, she eludes him. Finally, the hero is left alone with a remarkably unpleasant teacher of the tea ceremony, Kurimoto Chikako, also a former mistress of his father's, who has a large black birthmark on her breast. Kikuji's relationships with his dead father's mistresses and their daughter belie all that the tea ceremony represents - purity, serenity, harmony and sensitivity. It also shows the vulgarity into which the ceremony had fallen in modern Japan. The tea ceremony in this novel not so much provides a beautiful foil for ugly human affairs as serves to emphasize Kawabata's fascination with death: people die, but the vessels of tea remain, still bearing the marks of the dead (such as her mother's Oribe tea bowl Fujiko gives to Kikuji, which has a red glow on the rim that seems to be from lipstick). By the way, the way Mrs Ota has been depicted by Kawabata – always crying – is rather saccharine; despite the interesting theme, this is not one of Kawabata’s strongest novels.

[tr. Edward Seidensticker]

- Yama no oto ("The Sound of the Mountain," 1949-1954) is a complex novel - often considered Kawabata's best - about failed family relationships.

Shingo, an elderly businessman living in Kamakura (Kawabata's home from 1936 to his death) and nearing retirement, confronts several problems in his family, as well as the deaths of close friends which foreshadow his own nearing end. He is a lonely man who has little affection for others. He regards his wife as an object of amusement but certainly not of love - in fact, he used to be passionately in love with his wife's sister, who married another man and after that died at a still young age; Shingo often thinks about her. Next, the marriages of both his daughter and his son are in shambles. The daughter has left her husband and with her two children sought refuge with her parents. The son, who with his wife lives with his parents, dallies frequently with other women and has even got his mistress pregnant. Shingo is the only person in the family who has a close tie with the neglected wife of the son, his daughter in law (again, a woman he cannot have!). She seldom speaks her mind, but has built up so much hatred for her husband that she secretly has an abortion when she gets pregnant by him. Shingo contemplates moving back to the now empty family house in Nagano, but takes no action - this house may be symbolic for the ie, the large paternalistic family that was abolished after the war, and to which a return is impossible.

[tr. Edward Seidensticker]

(4) Tanizaki Junichiro writes one of his most beloved novellas, Shosho Shigemoto no haha ("Captain Shigemoto's Mother").

Placed in tenth century Kyoto, in the world of the Genji Monogatari which Tanizaki knew well thanks to his translation into modern Japanese. Begins with an account of the amorous exploits of a Heian Don Juan, called Heiju, after which it shifts its focus to three people: Shihei, the powerful Minister of the Left; his doddering uncle Kunitsune; and Kunitsune's ravishing and much younger wife, Tanizaki's omni-present femme fatale, who is known according to the custom of that time as “the mother of Captain Shigemoto.” In the course of a bizarre and drunken party Shihei manages to take Kunitsune's wife away and make her his own, in such a deft and tricky way that Kunitsune cannot even complain. Later, Kunitsune tries to kill his love for his absent wife by visiting a graveyard and meditating in a Buddhist way on the putrefying dead bodies he finds there. The latter part of the story is a brilliant culmination of Tanizaki's theme of love between mother and son. The concluding scene, in which mother and son are united, is very poetic. At the same time, Tanizaki introduces a new motif: the problem of sexuality in old age, that will be further developed in The Key and Diary of a Mad Old Man. The story has as little focus as its model, the Genji, and quotes lots of poetry, but that is also its charm.

[tr. Anthony H. Chambers in The Reed Cutter and Captain Shigemoto's Mother: Two Novellas]

5. Kikyo (“Homecoming”) by Osaragi Jiro was the first modern Japanese novel translated into English after WWII.

Osaragi Jiro (1897-1973) is primarily known as author of a large number of popular historical novels, but he also wrote contemporary novels, such as Homecoming, a glimpse into the soul of postwar Japan. Protagonist Kyogo has been forced into exile many years before the war by a scandal in the Japanese Navy. While hiding in Singapore during the war, he is betrayed to the Japanese Secret Police by a beautiful but shrewd diamond-smuggler, Saeko. After the war ends he is set free and travels to Japan to see what has become of his homeland. His wife has remarried (thinking him dead) and he is in the way of her husband, an opportunistic professor with political ambitions. He decides to leave Japan again – a country he now sees with the eyes of a foreigner, although he has also newly discovered the beauty of Kyoto – and not be an obstruction to anyone, but before leaving has a meeting with his now grown-up daughter, which allows him to reassure himself concerning her happiness. A similar novel about the anguish of intellectuals in postwar Japan by Osaragi is Tabiji (“The Journey”) from 1953, which has also been translated. American publishers started with "safe" middle-brow novels.

[tr. Brewster Horwitz]

1950

The Korean War begins.

The old practice of advancing one's age every New Year's Day (regardless of one's date of birth) is replaced by the western style of advancing one's age on each anniversary of one's date of birth.

On July 2 The Golden Pavilion (Kinkakuji) in Kyoto is burned to the ground by a 22-year-old novice monk.

(1) Ooka Shohei publishes his first novel, Musashino Fujin ("A Wife in Musashino"), the story of an ill-fated love between a young demobilized soldier, Tsutomu, and his married cousin, Michiko.

Michiko lives with her husband, Akiyama, in a house left to her by her father that is situated among the vestiges of an old forest in Musashino. Michiko is 29, and 41-year-old Akiyama is a French university teacher. Living across the road from Michiko and Akiyama are a businessman called Ono, his flashy wife Tomiko, and their daughter Yukiko. When the war ends, Michiko's cousin Tsutomu returns from Burma. As Yukiko's private tutor, Tsutomu comes to live in Michiko's house. Tsutomu's war-scarred psyche is soothed by long walks through the fields and forests of Musashino. When feelings of love blossom between Michiko and Tsutomu, this fans the flames of jealousy in both Tomiko, who has been trying to attract Tsutomu's attention, and Akiyama, who is naturally jealous of his wife. Consequently, Akiyama and Tomiko become involved with each other, and the two married couples become enmeshed in a tangled web of adultery and betrayal. The impact on Ooka of French writers such as Stendhal is apparent not only in his finely detailed observations of human emotions, but also in his critique of social customs and conventions. A film version by Mizoguchi Kenji of the novel was made a year after publication.

[tr. Dennis Washburn]

Ooka Shohei (1909-1988) was born in Tokyo and studied French literature at Kyoto University. He became an avid follower of Stendhal upon encountering his works after graduation. Drafted in 1944, Ooka was stationed in Mindoro in the Philippines, where he was captured by U.S. forces a year later and sent to a POW camp on the island of Leyte. After returning to Japan he wrote such novels as Furyoki ("Taken Captive") and Musashino fujin ("A Wife in Musashino") while also supporting himself as a translator. His other major works include Reite senki ("The Battle of Leyte Gulf"), Nobi ("Fires on the Plain"), his masterwork, and Kaei ("The Shade of Blossoms").

[Study: The Burden of Survival, Ooka Shohei's Writings of the Pacific War by David C, Stahl, Hawaii U.P.]

(2) The second novel by Mishima Yukio appears: Ai no kawaki ("Thirst for Love").

A work set in post-war Japan, portraying a young widow's loss of moral direction. After her husband's death, Etsuko goes to live in her father-in-law's household, only to be forced to become the old man's mistress. She falls crazily in love with a farm boy, Saburo, especially when she sees him half-naked at a frenzied Shinto festival (Mishima's impersonation of Etsuko in a scene like this has been called "Mishima in drag" by Donald Keene). But Saburo is more interested in one of the servant girls. When Etsuko finally attempts to force herself on the boy, she looses heart and calls for help, pretending that Saburo is trying to rape her. Her father-in-law appears with a scythe, which Etsuko snatches from his hand to kill Saburo. There is a beautiful, modernist film version by Kurahara Koreyoshi with Asaoka Ruriko as Etsuko.

[tr. Alfred H. Marks]

[Reference works used: Dawn to the West by Donald Keene (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984); Modern Japanese Novelists, A Biographical Dictionary by John Lewell (New York, Tokyo and London: Kodansha International, 1993); Narrating the Self, Fictions of Japanese Modernity by Tomi Suzuki (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996); Oe and Beyond, Fiction in Contemporary Japan, ed. by Stephen Snyder and Philip Gabriel (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999); Origins of Modern Japanese Literature by Karatani Kojin (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993); The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature, 2 vols, ed. by J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005 and 2007); The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature by Susan J. Napier (London and New York: Routledge, 1996); Writers & Society in Modern Japan by Irena Powell (New York, Tokyo and London: Kodansha International, 1983).]

[All photos public domain from Wikimedia Commons]